![]()

Is Hubal The Same As Allah?

Islamic Awareness

© Islamic Awareness, All Rights Reserved.

First Composed: 24th April 2006

Last Modified: 20th January 2008

| Tweet |

|

|

36Save |

Assalamu-ʿalaykum wa rahamatullahi wa barakatuhu:

The Christian missionaries have argued over many years that "Allah" of the Qur'an was in fact a pagan Arab "Moon god" of pre-Islamic times. The primary proponent of this view was Robert Morey, and, along with his missionary brethren, he has propagated these views extensively. We have made a devastating refutation of this claim by utilising the archaeological evidence showing that his claims were nothing but a grand fraud. In the meantime, however, the missionaries have continued their idol speculation and came up with yet another allegation concerning the genuine monotheistic origins of Allah. This time it is alleged that Allah and Hubal, the principal idol of pre-Islamic times located in Makkah, are one and the same entity. Furthermore, they claim that "Muhammad's Allah is actually Hubal, i.e. the Baal of the Moabites". According to them “Hubal being the Arabic for the Hebrew HaBaal, "the Baal."” Morey's disastrous foray into ancient Near-Eastern religions and other related disciplines has not dissuaded like-minded Christians to construct similar lunar fantasies. Just like his "Moon god" allegation, the missionaries have also claimed that Hubal was a Moon-god, and by identity Allah also was a Moon-god. Recently, Timothy Dunkin, an ardent supporter of Morey and his "scholarship", has attempted to summon the scholarly literature to show Hubal had been considered as Allah all along, claiming to have advanced scholarly investigation in the process.

Are these claims of the Christian missionaries true? In this article we would like to examine the nature of Allah and Hubal from the historical, lexical and archaeological point of view. We will show the claim that Allah and Hubal are identical, is untenable not only from the point of view of history but also from archaeology. A lexical and epigraphic study will confirm that Hubal and "Ha-Baal" are different deities. Regrettably, one will observe those defective academic trends observed in previous lunar reconstructions such as fabricating evidence, misquoting sources and inability to consistently cite the correct bibliographic references, continues unabashed.

2. Hubal = Allah? A Detailed Investigation

The Quraysh had several idols in and around the Kaʿbah. The greatest of them was Hubal. Its cornelian or agate statue stood inside the Kaʿbah. The statue of Hubal was of a male figure with a golden arm - a replacement of a broken-off stone arm when Hubal came into possession of the Quraysh. ʿAmr ibn-Luhayy imported Hubal and it was first set up by Khuzaymah ibn Mudrikah ibn al-Ya's ibn Mudar. Consequently, it used to be called Khuzaymah's Hubal.[1] In front of Hubal there were seven divination arrows. A custodian guarded the statue, received the offerings and sacrifices and conducted future-forecasting to pilgrims. The cult associated with him involved divination and forecasting of future events such as marriage, death, apology, lineage, etc.[2] ʿAbd al-Muttalib, grandfather of the Prophet Muḥammad, shuffled the divination arrows in order to find out which of his ten children he should sacrifice in fulfilment of a vow. The arrow pointed to his son ʿAbdullah, father of Muḥammad. The Quraysh deterred the Prophet's grandfather, arguing that his act would establish an example that other Arabs might follow.

It was mentioned that ʿAmr ibn-Luhayy imported Hubal to Makkah. What were the origins of Hubal?

According to the Christian missionary Nehls, in an attempt to connect Hubal with "Ha-Baal" (i.e., the Baal), the Hubal idol at Makkah must have originated from Moab. He says:

Where was Baal worshipped? In Moab! It was the "god of fertility". Amr ibn Luhaiy brought Hubal from Moab to Arabia.

Not surprisingly, he did not mention any supporting evidence to prove that the Islamic traditions say that ʿAmr ibn Luhayy brought the Hubal idol from Moab to Arabia. The missionaries lifting each others work without proper verification is not entirely surprising. Yet another missionary lifted Nehls' claim about the origins of the Hubal idol at Makkah from Moab, only to present a quote from Hitti's History Of The Arabs that says ʿAmr ibn-Luhayy imported the Hubal idol "from Moab or Mesopotamia";[3] thus clearly throwing uncertainty over the Moabite origins of Hubal. From the Islamic traditions, it is unclear where the Hubal idol in Makkah originated from. Al-Azraqi says ʿAmr ibn Luhayy brought Hubal from Hit in Mesopotamia, a town situated on the Euphratus,[4] while Ibn al-Kalbi implied that it came from al-Balqa' in Bilād al-Shām.[5] Ibn Hisham[6] and Ibn Kathir,[7] on the other hand, say that it came from Moab in the land of Balqa' in Transjordan. There is no clear-cut position that can be adduced from the Islamic traditions on the issue of the place of origin of the Hubal idol at Makkah, although all of them are united on its foreign origin.[8] There was an awareness among the pre-Islamic Arabs that Hubal was an imported deity and this partly explains why he was not integrated into the "divine family" of Allah unlike the three "daughters of Allah", Allat, Manat and al-ʿUzza. This brings us directly to the issue of whether or not Hubal was nothing but Allah. First of all let us take a glimpse into the methodologies adopted by anti-Islamic polemicists concerning the identity of Hubal with respect to the Islamic sources.

CARLETON COON, ISLAMIC SOURCES & HUBAL

There are primarily two methodologies used by anti-Islamic polemicists in an attempt to prove that Hubal is none other than Allah. One of them is denying entirely the authenticity of the Islamic sources concerning Hubal, instead relying upon speculation with an option of picking and choosing what appears most suitable from the Islamic sources. The other method is to simply play around with the content of the Islamic sources. The Christian apologist Dunkin has adopted the former haphazard approach which involves denying the authenticity of the Islamic sources. The way he achieves this is to resurrect a specific statement of Carleton Coon, upon which his entire argument is underwritten. He says quoting Carleton Coon:

Moslems are notoriously loath to preserve traditions of earlier paganism, and like to garble what pre-Islamic history they permit to survive in anachronistic terms.

With such an introduction, the apologist hoped to present a "refutation" of our claims concerning Hubal and then provide some "insights" which will encourage scholarly investigation. However, there are a couple of serious problems with the use of Coon's quote in connection with Hubal. Firstly, Coon's discussion is confined to southern Arabia, as the title of his paper "Southern Arabia, A Problem For The Future" clearly indicates. Hubal, on the other hand, was a north / central Arabian deity which does not even figure in epigraphic South Arabian. So, Coon's quote concerning the alleged garbling of pre-Islamic paganism by Islamic sources has nothing to do with Hubal. If we look at his quote in context what we read is:

The religion of these southern Arabian states, so intimately entwined with the social and political structure, is not easy to reconstruct. Moslems are notoriously loath to preserve traditions of earlier paganism, and like to garble what pre-Islamic history they permit to survive in anachronistic terms. Our religious sources, then, are confined to the body of inscriptions so far published, and a few superficial Greek observations.[9]

Clearly, Coon is talking about the religious sources of ancient South Arabia which are inscriptions and Greek-related sources in which Hubal does not even figure. Secondly, one can argue the basis of Coon's dismissal of the value of the Islamic traditions on the basis of its own merits. What are the evidences which Coon considers to claim that Islamic sources present a garbled picture of pre-Islamic paganism? According to Coon, the section ("The Pre-Islamic Kingdoms") from which the above mentioned quote is taken, is based on the work of Ditlef Nielsen. Coon plainly says:

The literary evidence upon which much of this section is based is drawn largely from Nielsen, et al., 1927.[10]

Furthermore, in the same section, Coon highlights the discussion on the South Arabian kingdoms, their boundaries in space and time, their social structures, their religious practices and their economic life, by mentioning that:

With the aid of prodigious scholarship of Nielsen and his associates, we will proceed to discuss these in brief... It is possible, as Nielsen has done, to fit this whole religious system as we known it on the basis of incomplete evidence, into the general Semitic scheme, in which the four kingdoms of southern Arabia, and the northern Arabs as well, become the southern branch, and the Phoenicians, Babylonians, Assyrians, etc., the northern with the Jews playing a mixed role.... For the present purposes it must be considered sufficient to have presented the foregoing brief and unscholarly resumé of the work of Nielsen and his associates, as a summary of present knowledge of this intensely interesting and important archeological problem.[11]

To put everything succinctly, Coon's claim that Islamic sources present a garbled picture of pre-Islamic paganism is not based on comparing the evidence from the Islamic sources vis-à-vis the South Arabian epigraphic material. Rather it is based on the belief that since Nielsen and his associates were correct in their assessment of ancient South Arabian religion, the Islamic sources must have presented a garbled picture of pre-Islamic paganism. But now we know that the reduction of the pantheon of ancient Near Eastern divinities to a triad by Nielsen was not based on actual evidence but mere speculation which made his theories dubious which consequently invited incisive rejoinders from 1924 onwards. What now becomes peculiar is that Dunkin himself admits to the rejection of Nielsen's theories by saying:

Likewise, while it is true that Nielsen's particular theory about astral triads in Arabian religion was overstated and has rightly been rejected, this does not mean that there was no astral, and especially lunar, character to pre-Islamic Arabian religion...

Yet he as no problem accepting Coon's allegation regarding the unreliability of Islamic sources concerning pre-Islamic paganism which is simply based on the belief that Nielsen was correct in his hypothesis concerning astral triads in ancient South Arabian religion! Has Dunkin even read Coon's paper? Holding such contradictory positions, the Christian apologist then states that he considers the Muslim traditions as "fictitious" – and it is here we arrive most abruptly at a common fallacy in modern Islamic studies known as "appeal to Schacht". Merely invoking his name and summarising his main hypotheses is sufficient to dismantle any historical edifice that could possibly remain in the Islamic sources. Western scholars have accepted for quite some time now that such uncritical adherence to the Schachtian framework does not suffice any more in serious academic discourse;[12] to do so is to disengage with the evidence one is not willing to confront, either due to inherent prejudices in methodology or distaste in the final result.[13] If Schacht is mentioned then John Wansbrough, who based some of his hypothesis on Schacht's conclusions, can't be far. According to Wansbrough, the theories that emerge from his analysis are, in his own words "conjectural",[14] "provisional"[15] and "tentative and emphatically provisional".[16] It seems that use of such "conjectural", "provisional" and "tentative and emphatically provisional" theories does not trouble Dunkin. Instead he is all too eager to embrace them to "prove" with certainty that the Islamic traditions are not authentic.

To enlighten the Christian apologist who is adept at quoting people without understanding their position or the position of modern ḥadīth scholarship, it must be pointed out that Wansbrough and his ilk had relied on the work of Joseph Schacht and considered that Schacht had sufficiently proven the unreliability of Muslim traditions. However, in the last two decades a considerable amount of progress has been made in Western scholarship on ḥadīth. This is due to two reasons: Firstly, the availability of new sources that are "pre-canonical" such as the Muṣannafs of ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿānī and Ibn Abī Shayba or ‘Umar bin Shabba's Tārīkh al-Madīnah (Schacht had no access to earlier sources); and secondly, the development of isnād and matn analysis of the aḥādīth that resulted in the investigation of textual variants of the aḥādīth. Using this technique, aḥādīth have been shown to have very early origins going back to the 1st century of hijra.[17] The earliest Arabic literature that comes to us is in the form of ḥadīth collections. An example is the Ṣaḥifah of Hammām bin Munabbih, [d. 110 AH / 719 CE], a Yemenite follower and a disciple of the companion Abu Hurrayrah, [d. 58 AH / 677 CE], from whom Hammām wrote this Ṣaḥifah, which comprises 138 aḥādīth and is believed to have been written around the mid-first AH / seventh century. This is available as a printed edition.[18] The ḥadīth collections of Ibn Jurayj [d. 150 AH] and Maʿmar b. Rāshad [d. 153 AH], many of them transmitted by ʿAbd al-Razzāq in his Muṣannaf, are also available in print.[19] Motzki has traced the material in the Muṣannaf of ʿAbd al-Razzāq to the first century of hijra.[20]

Given such a poor understanding and even ignorance of modern ḥadīth scholarship, Dunkin has the audacity to talk about the "kernel of truth" which he can see "lying at the heart of some of the statements made in the traditional materials that pertain to our present study". As to by what methodology one can discern the "kernel of truth" is not discussed and yet there is talk of exercising "enough critical faculty to strip away the chaff that surrounds the kernel". As for stripping away that chaff from the kernel, we have already shown some examples of it and there are more to come in the following sections.

HUBAL AND “SONS AND DAUGHTERS” OF ALLAH

Allat, al-ʿUzza and Manat, the three female goddess of pre-Islamic Arabia, are mentioned in the Qur'an. The notable exception to this is Hubal, whom many consider to be a central figure in the Arabian hierarchy of gods. Why is Hubal, considering he was a prominent figure in the pantheon of gods and goddesses, not mentioned in the Qur'an? This question in itself has raised many more questions, causing many Orientalists to indulge themselves in unreserved speculations. Perhaps the earliest scholar to suggest that Hubal was originally the proper name of Allah in Makkah was the German orientalist Julius Wellhausen. His hypothesis was based on circumstantial evidence and argumentum e silentio. Wellhausen noted that Allah was always a proper name in the Arabic sources and not a common noun. According to him, Allah was the title used within each tribe to address its tribal deity instead of its proper name[21] and that Allah became the Islamic substitute for the name of any idol.[22] Wellhausen suggested that apart from Hubal's known presence in the Kaʿbah, there is no polemic in the Qur'an against him.[23] In other words, while the Qur'an railed against Allat, Manat, and al-ʿUzza, whom the pagan Arabs referred to as the "daughters of Allah", it stopped short of attacking the cult of Hubal. Although such an argument can be applied to any of the pagan idols not mentioned in the Qur'an, such as Dhul-Khalasa and Dhul-Shara, the argumentum e silentio of Wellhausen became a rallying cry for the missionaries and apologists to claim that Hubal was none other than Allah.[24] This is clearly a logical fallacy. It is ironical that the Qur'an itself is ignored to address the issue of Hubal. As mentioned earlier, there were three prominent deities of ancient Arabia mentioned in the Qur'an.

Have you then considered Allat and the ‘Uzza, and Manat, the third, the last? What! for you the males and for Him the females! This indeed is an unjust division! They are naught but names which you have named, you and your fathers; Allah has not sent for them any authority. They follow naught but conjecture and the low desires which (their) souls incline to; and certainly the guidance has come to them from their Lord. [Sūrah al-Najm:19-23]

The reason why Hubal is not mentioned is specifically because of his gender. There was nothing to distinguish Hubal from the other Arab divinities such as Dhul-Khalasa and Dhul-Shara whereas other divinities mentioned in the Qur'an, i.e., Allat, Manat and al-ʿUzza, were distinguished by being regarded as the "daughters of Allah", as pointed out by Fahd although he did not completely elaborate this important point.[25] Similarly, the Qur'an also criticizes the position of the "sons of Allah" attributed to Jesus and ʿUzayr. In Sūrah al-Najm, the Qur'an is referring to the concept of "daughters of Allah", and to mention a male deity like Hubal would be against the very argument the Qur'an is drawing attention to.

What! for you the males and for Him the females! This indeed is an unjust division! [Sūrah al-Najm:21]

The Qur'an uses irony to drive home a point. While many of the Arabs buried their daughters alive, as well as holding the position that women were inferior to men in all aspects, they still fabricated daughters for Allah. The first point which the Qur'an mentions is that they have no evidence for their speculations:

They are naught but names which you have named, you and your fathers; Allah has not sent for them any authority. They follow naught but conjecture and the low desires which (their) souls incline to; and certainly the guidance has come to them from their Lord. [Sūrah al-Najm:23]

Secondly, what is interesting is that while this verse attributes this position to conjecture, it further explains the psychological reason behind the conjecture. Conjecture is the project of an overpowering emotion and desire. A person seeks all types of justifications for his behaviour, because he wants to act in a certain way. What exactly were the desires that caused the Arabs to conjecture regarding female idols Allat, al-ʿUzza, and Manat? Those who take their desires as gods, end up personifying these desires in idol form, fulfilling the words of the Qur'an

Have you seen him who takes his desires as god?" [Sūrah al-Jathiya:23]

The main irony in the concept of intercession of the Arabs was that the women in Arabian society did not hold any real position of influence in their society. Yet, the female deities, according to the Arabs, had the station with Allah to influence His decisions! As compared with Allat, Manat, and al-ʿUzza, Hubal lacks specific connective attributes. He was a male with a golden arm - a replacement of a broken-off stone arm when Hubal came into possession of the Quraysh. Hubal's cult associated with him involving divination and forecasting of future events. The idolaters most momentous claims were reserved for other idols which they claimed held a specific station and divine intimate connection with Allah.

Dunkin stated Hubal (read Allah) was the

result of a long process of evolution from the Ba'al deities of other lands… This association would have been based upon similarities of station and function held in common by these gods in each area.

It should come as no shock that these unnamed and unknown Baʿal deities are never mentioned nor are the regions they came from. On only one occasion do we find Dunkin referring to a "station and function held in common". Noting that the polytheists attributed three daughters to Allah, Dunkin saw a connection with Baʿal, a deity mentioned in the late Bronze Age cuneiform alphabetic texts discovered in 1928 at Ras Shamra, Syria, because he had three daughters. On the basis of this single piece of information Dunkin readily identifies Baʿal with Allah. Not dissimilar to his other startling claims, he posits no evidence whatsoever for this assertion, other than alluding to "some modifications and evolution" which allowed Baʿal to become Allah "with three daughters". With these few words Dunkin rescues himself from properly evaluating the substance of his claim, hoping to capture an air of credibility by making a passing reference to Baal In The Ras Shamra Texts. In this book Kapelrud explains that Baʿal's family consisted of father, mother, brothers, sisters and son[26] as well as various helpers and messengers.[27] Dunkin's lack of critical insight extends further than the misappropriation of Baʿal's family. The Ugaritist Cyrus Gordon briefly studied the geographic origin of the so-called "daughters" of Allah and concluded the names in the triad bore no resemblance with the daughters of Baʿal, whilst pointing out Allah and Baʿal Shamen were "rival deities".[28]

Gordon was writing just fifteen years after the texts at Ras Shamra had been discovered. Not until very recently has a comprehensive study of all the epithets of the attested Ugaritic deities been published.[29] The significance of such a study is that the epithets of all the individual Ugaritic deities mentioned in the cuneiform alphabetic texts from Ras Shamra and Ras Ibn Hani are discussed in context, allowing one to draw conclusions about a particular deity based on its respective epithets in light of the epithets of the other deities. Baʿal had fourteen epithets.[30] Rahmouni emphasises the importance of the epithets as they "reflect the basic religious concepts of Ugaritic society and help us to determine the role and position of the various gods in Ugaritic religion".[31] She goes on to say, "The study of different epithets of the same god in different contexts helps us to determine the god's characteristics and functions, …".[32] Proceeding from this starting point we learn the most common Ugaritic divine epithet "Baʿlu the mighty one" refers to his victories over rival deities Yammu and Môtu – deities which also defeat Baʿal on occasion.[33] The limited kingship of Baʿal is dependant on and is exercised under the supreme authority of the deity ʾIl, who is the only deity that can appoint another deity as king. Baʿal has to compete for kingship with other deities. Baʿal has no authority over the creation of mankind or other deities. Baʿal has a filial relationship to Dagānu. In addition to the family relationships mentioned earlier, Baʿal has a son-in-law which refers to the god Yrh who apparently wed Pdry, the daughter of Baʿal. Along with all other deities, Baʿal relies on ʾIl for strength and encouragement and is filially related to him. Baʿal is forced to surrender to and is defeated by other deities he battles with. Baʿal has a consort, the goddess ʿAnatu.[34] Such attributes have never been associated with Allah. Even more telling is the theology of Baʿal[35] and the cultic and ritual practices at Ugarit,[36] from which one could make several dozen observations. It will be sufficient to mention just one aspect here pertinent to the topic raised. Baʿal is a dying or disappearing god.[37] One would be hard pressed to find a greater antithesis to the Islamic creed. In fact just a few hundred kilometres south-east of Ras Shamra in Jabal Usays (also in Syria), the first line of one of the most imperative verses in the Qur'an, ayat al-Kursi (2:255), lays inscribed on a rock face. Dated to the year ninety-three of hijra, Allah is described as the Ever-Living, the One who sustains and protects all that exists.[38] One may point to an even earlier inscription dated twenty-nine of hijra from Cyprus containing Sūrah al-Ikhlaṣ where Allah is described as one, eternal/absolute, who begets not nor is begotten and is incomparable. There can be no greater contrast. As has been observed, Dunkin's proposed falsification of the literary texts by later Muslims in order to eradicate the pagan origin and nature of Allah is contradicted by the documentary evidence which merely confirms what the literary sources already tell us,[39] not to mention the Ugaritic materials that he dismally failed to assess and comprehend.

Do contemporary non-Muslim sources provide any inkling of Baʿal worship and/or idolatrous syncretism before, during or after the time period which Dunkin thinks the later Muslims allegedly started falsifying their literary sources to conceal the pagan origin and nature of Allah? A close examination of over one hundred sources written in languages including Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Persian and Chinese from of a variety of different literary genres written from both within and out with the Islamic state, reveals there is no evidence to suggest Baʿal worship was practised amongst the early Muslims or that Hubal was ever considered as Allah.[40] In fact, the earliest Christian writings clearly depict Muḥammad as a monotheist revivalist who drew his people away from idol worship,[41] just the opposite of what Dunkin had suggested. Writing some twenty-eight years after Muḥammad had died during the end of the caliphate of Ali c. 660 CE, the Armenian chronicler Sebeos says the "Ishmaelite called Mahmet" turned his people away from vain cults towards the worship of the living god who had revealed himself to Abraham. Also writing c. 660 CE, the chronicler of Khūzistān likewise comments on the ancestral Abrahamic connection. Writing during the caliphate of ʿAbd al-Malik, c. 687 CE, John bar Penkaye wrote, "As a result of this man's guidance they held to the worship of the one god in accordance with the customs of ancient law". Archdeacon George writing in the early eight century said, "he returned the worshippers of idols to the knowledge of the one God". In the last quarter of the eighth century the Chronicle of Zuqnin, composed by a resident of a monastery of that name in Mesopotamia said, "he had turned them away from the cults of all kinds and taught them that there was one God, maker of Creation".[42] The founder of Christian apologetic and anti-Islamic polemic John of Damascus (c. 655 – 750 CE) placed at the head of his discussion of Qur'anic doctrine Sūrah al-Ikhlaṣ, which it seemed he considered the core Qur'anic message.[43] He even had a positive recognition of Muḥammad as the person who had led his people back to monotheism from all kinds of idolatry.[44]

In his effort to provide a direct comparative analysis of different regions, cultures, languages and religions spanning several millennia, something which is cautioned against by the very source he thought provided support for his views,[45] Dunkin's contribution is thin on evidence and thick on speculation and misunderstanding. Let us now move on to more fruitful ground and consider what the Islamic traditions tell us about Hubal and Allah.

THE IDENTITY OF ALLAH AND HUBAL ACCORDING TO ISLAMIC TRADITION

The hypothesis that Hubal was originally the proper name of Allah suffers from serious difficulties. In the battle of Uhud, the distinction between the followers of Allah and the followers of Hubal is made clear by the statements of Prophet Muḥammad and Abu Sufyan. Ibn Hisham narrates in the biography of the Prophet:

When Abu Sufyan wanted to leave he went to the top of the mountain and shouted loudly saying, 'You have done a fine work; victory in war goes by turns. Today in exchange for the day (of Badr). Show your superiority, Hubal,' i.e. vindicate your religion. The apostle told ‘Umar to get up and answer him and say, God [Allah] is most high and most glorious. We are not equal. Our dead are in paradise; your dead are in hell.[46]

The same incident is narrated in Ṣaḥīh of al-Bukhari with a slightly different wording (for a more detailed narration see here).

Abu Sufyan ascended a high place and said, "Is Muhammad present amongst the people?" The Prophet said, "Do not answer him." Abu Sufyan said, "Is the son of Abu Quhafa present among the people?" The Prophet said, "Do not answer him." Abu Sufyan said, "Is the son of Al-Khattab amongst the people?" He then added, "All these people have been killed, for, were they alive, they would have replied." On that, 'Umar could not help saying, "You are a liar, O enemy of Allah! Allah has kept what will make you unhappy." Abu Sufyan said, "Superior may be Hubal!" On that the Prophet said (to his companions), "Reply to him." They asked, "What may we say?" He said, "Say: Allah is More Elevated and More Majestic!" Abu Sufyan said, "We have (the idol) al-‘Uzza, whereas you have no ‘Uzza!" The Prophet said (to his companions), "Reply to him." They said, "What may we say?" The Prophet said, "Say: Allah is our Helper and you have no helper."

The isnād bundle of these aḥādīth can be depicted as shown below. It was drawn using Ḥadīth Sharīf software by al-Sakhr as well as by referring to the books of aḥādīth.

Commenting on the above tradition that specifically distinguishes and contrasts between the worshippers of Allah and the worshippers of Hubal, Dunkin says:

These traditions are simply untrustworthy, and most likely represent polemical inventions by later Muslims to serve as object illustrations of the victory of Allah over the Jahiliya pagan system. The story in which Abu Sufyan cries, "Be thou exalted, Hubal!", and Mohammed replies, "Be thou more exalted, Allah!", is programmatic in its polemical presentation. This is especially so when we consider the addendum to this story, also adduced by Saifullah and David, in which Abu Sufyan holds a meeting with Mohammed and realizes the error of his previous ways, and becomes a good Muslim. The traditional literature of Islam abounds with this sort of story, in which pagans and apostates realize their error and "revert" to Islam as the only and obviously true way. There is simply no good reason to rely upon the traditions about Abu Sufyan and his (and Hubal's) opposition to Allah as any sort of truly historical set of events, especially in light of the rest of the opposing evidences...

The traditions which deal with Hubal, while showing a great amount of redaction by later Muslims, nevertheless still contain a core of information that helps to show us that Hubal was understood to be the Lord of the Ka'bah.

Dunkin brushed aside what did not suit his fancy as "untrustworthy" and a "polemical invention" by "later Muslims". Concerning as to who invented the story, why it was invented and where it was invented, the Christian apologist is remarkably silent, yet he is still able to proclaim with confidence a "great amount of redaction" has taken place!

As a formal discipline, redaktionsgeschichte (redaction criticism / redaction history), a term coined by Professor Willi Marxsen in 1954, is a recent construction and was originally developed by biblical scholars to aid the study of the New Testament text, and in particular the synoptic Gospels. Although it is difficult to find any one agreed upon definition, the generally stated purpose of this method is to study the way in which authors changed their sources; it is therefore a method which focuses upon the stages of the editorial process which might reveal something of the redactor's theology and/or intentions.[47] There is intense debate as to the usefulness of this historical critical method and what value, if any, it holds in unlocking some of the textual problems of the New Testament, especially so amongst evangelicals.[48] By definition, therefore, before any claim of "redaction" and its alleged implications can be made, it is incumbent on the assessor to have sufficiently studied the authors, transmitters and collectors of the material, their respective texts and how they are expressed.[49] Dunkin claims to have found a "great amount of redaction" in the traditions concerning Hubal which presupposes the apologist has collated and analysed the relevant ḥadīth compilations dealing with the Hubal traditions. The apologist has not provided any evidence of the former thus immediately betraying his own claims as bogus. Nevertheless, let us now take the opportunity to have a comprehensive look at the sources, their transmitters and collectors to establish if any such "redaction" has occurred.

Isnād bundle of this ḥadīth and its variants in the form of a slightly different text shows an interesting picture, quite contrary to what Dunkin had claimed. This ḥadīth has come to us from four independent sources, i.e., al-Barā'a ibn ʿAzib, ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbbās, ʿAbdullāh ibn Masʿūd and ʿUrwa ibn al-Zubayr. It was recorded by Sulaymān ibn Dāwūd al-Ṭayālisī [d. 203 AH / 819 CE] in his Musnad, ʿAbd al-Razzāq [d. 211 AH / 826 CE] in his Muṣannaf, Ibn Abi Shayba [d. 235 AH / 849 CE] in his Muṣannaf, Ahmed ibn Hanbal [d. 241 AH / 855 CE] in his Musnad, al-Bukhārī [d. 256 AH / 870 CE] in his Ṣaḥīḥ, Abū Dāwūd [d. 275 AH / 888 CE] in his Sunan, al-Nasā'ī [d. 303 AH / 915 CE] in his Sunan apart from others like al-Ruyanī and Abū ʿAwanah. Ahmed ibn Hanbal has collected this narration from all of the sources except one whereas ʿAbd al-Razzāq collected his material from only one source, i.e., ʿUrwa ibn al-Zubayr.

What about the dating of this tradition?

This isnād bundle shows that the earliest known occurrence of this ḥadīth is in the Musnad of al-Ṭayālisī [d. 203 AH / 819 CE]. In other words, this ḥadīth was already known and in circulation in the early third Islamic century, if we consider the death of al-Ṭayālisī as a terminus post quem.

Is that the final word on the dating of this ḥadīth? An analysis of the isnād bundle suggests that the tradition from al-Barā'a ibn ʿAzib intersects at Zubayr ibn Muʿawiya [d. 174 AH / 790 CE]. He is the common link.

One can claim that Zubayr ibn Muʿawiya might have invented this distinguishing tradition between Hubal and Allah, thereafter circulating it widely as he was the common link.[50] However, there are arguments which speak against the assumption that Zubayr invented this information outright. A tradition from al-Bukhārī circumvents Zubayr ibn Muʿawiya and comes via ʿAmr ibn ʿAbdullāh [d. 127 AH / 745 CE] in a slightly shorter form. Therefore, this tradition was already known in the first quarter of the second century of hijra. It can be corroborated by the fact this tradition with a slighty longer text also occurs in the Muṣannaf of ʿAbd al-Razzāq al-Ṣanʿānī [d. 211 AH / 826 CE] and was independently transmitted via the isnād Maʿmar b. Rāshad [d. 153 AH / 770 CE] ![]() Muḥammad ibn Muslim, i.e., Ibn Shihab al-Zuhrī [d. 124 AH / 741 CE]

Muḥammad ibn Muslim, i.e., Ibn Shihab al-Zuhrī [d. 124 AH / 741 CE] ![]() ʿUrwa ibn al-Zubayr

[d. 94 AH / 712 CE]. Hence it can be safely said that this tradition was already known to al-Zuhrī who died a few years before ʿAmr ibn ʿAbdullāh. Likewise, a similar point can be made concerning ʿAbdullāh ibn Dhakwān [d. 130 AH / 748 CE] who again independently transmitted this tradition of ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbbās. Furthermore, ʿAmr ibn ʿAbdullāh and Muḥammad ibn Muslim directly received the traditions from the al-Barā'a ibn ʿAzib [d. 72 AH / 692 CE] and ʿUrwa ibn al-Zubayr [d. 94 AH / 712 CE], respectively, thereby representing the shortest isnād going back to the actual source. Thus it can be safely concluded that this tradition goes back to the first century of hijra. With the independence of sources as well as transmitters of this ḥadīth, it is hard to believe Dunkin's claim of its "untrustworthy" and a "polemical invention" by "later Muslims". Study of the matn (i.e., the text of the ḥadīth) from the four independent sources clearly shows that they are talking about one and the same event, and in particular, a clear distinction between the followers of Allah and followers of Hubal is demonstrated, with an addition or subtraction of the details in the text. Such an omission or addition occurs in the ḥadīth literature and does not constitute "redaction".

ʿUrwa ibn al-Zubayr

[d. 94 AH / 712 CE]. Hence it can be safely said that this tradition was already known to al-Zuhrī who died a few years before ʿAmr ibn ʿAbdullāh. Likewise, a similar point can be made concerning ʿAbdullāh ibn Dhakwān [d. 130 AH / 748 CE] who again independently transmitted this tradition of ʿAbdullāh ibn ʿAbbās. Furthermore, ʿAmr ibn ʿAbdullāh and Muḥammad ibn Muslim directly received the traditions from the al-Barā'a ibn ʿAzib [d. 72 AH / 692 CE] and ʿUrwa ibn al-Zubayr [d. 94 AH / 712 CE], respectively, thereby representing the shortest isnād going back to the actual source. Thus it can be safely concluded that this tradition goes back to the first century of hijra. With the independence of sources as well as transmitters of this ḥadīth, it is hard to believe Dunkin's claim of its "untrustworthy" and a "polemical invention" by "later Muslims". Study of the matn (i.e., the text of the ḥadīth) from the four independent sources clearly shows that they are talking about one and the same event, and in particular, a clear distinction between the followers of Allah and followers of Hubal is demonstrated, with an addition or subtraction of the details in the text. Such an omission or addition occurs in the ḥadīth literature and does not constitute "redaction".

Going back to the actual text of the ḥadīth, one can see clear facts emerging. Firstly, the Quraysh worshipped Hubal and al-ʿUzza (among other deities not stated here); the Muslims, on the other hand, worshipped Allah. Secondly, with regard to the statement of Abu Sufyan ascribing superiority to Hubal, Prophet Muḥammad replied that Allah was more Majestic and more Glorious. Thirdly, the dead of the pagan Quraysh in the Battle of Uhud who worshipped Hubal, al-ʿUzza among other gods are in the hell, whereas the dead who worshipped Allah are in heaven. Fourthly, the worshippers of Allah are not equal to the worshippers of Hubal. Since the Christian missionaries have a habit of using a syllogism even though there are clear statements refuting their position, let us note the following syllogism.

Commenting on the above tradition, the Christian missionaries say:

Unlike the verse in the Quran, this one does mention Hubal by name and suggests that he was distinct from Allah. Again, Muhammad transforming Allah from a pagan deity into the sole universal God, a transformation which was different from any similarly named deity, can account for why Sufyan viewed Hubal as a different god altogether.

Furthermore, this tradition actually poses problems for the Muslims since it implies that the pagans such as Abu Sufyan did not view Allah as the supreme god, but one of many rival gods. Sufyan attributes his victory over Muhammad and his god to Hubal and Uzza, suggesting that at least in his mind these gods were equal, if not superior, to Allah. Sufyan obviously felt that Allah could be challenged and defeated, which means that these pagans didn't see Allah as the unrivaled and supreme Deity as both the Quran and Islamic traditions claim.

It is hard to see how this tradition poses "problems" for Muslims. In fact, this tradition clearly refutes the missionaries' claim that Allah and Hubal were identical. Furthermore, Abu Sufyan, the chieftain of the Quraysh, became a Muslim in 8 AH just a few days before the liberation of Makkah, after a personal council with the Prophet.[51] He swallowed his pride and admitted that:

By God, I thought that had there been any God with God, he would have continued to help me.[52]

In other words, Hubal and al-ʿUzza which Abu Sufyan had proclaimed as gods neither assisted nor helped him to defeat the Muslims. He then accepted Allah as the one, supreme God beside whom there exists no other god. Furthermore, he was also personally involved in the smashing of the idol of Allat, one of the so called daughters of Allah.[53] It must also be added that if the idol of Hubal which occupied the Kaʿbah in Makkah represented the image of Allah, then why did Muḥammad order it to be destroyed? He could easily have left the statue as it was and justified it as the image of Allah, thus making it far easier for those transitioning from polytheism to monotheism. History records this never happened, rather Muḥammad ordered all the idols destroyed. It is not difficult to see why this is the case if one pays attention to the Islamic sources, especially those which inform us directly about the life and times of Muḥammad. Consider the following. The most supreme delight in the afterlife is the ability to see Allah. Anticipating this humbling and blissful moment is a source of immense joy and happiness for all the believers.[54] We find narrated in the Ṣaḥīh of al-Bukhari the following report:

On the authority of Abu Huraira: The people said, "O Allah's Apostle! Shall we see our Lord on the Day of Resurrection?" The Prophet said, "Do you have any difficulty in seeing the moon on a full moon night?" They said, "No, O Allah's Apostle." He said, "Do you have any difficulty in seeing the sun when there are no clouds?" They said, "No, O Allah's Apostle." He said, "So you will see Him, like that. Allah will gather all the people on the Day of Resurrection, and say, 'Whoever worshipped something (in the world) should follow (that thing),' so, whoever worshipped the sun will follow the sun, and whoever worshiped the moon will follow the moon, and whoever used to worship certain (other false) deities, he will follow those deities...

The importance of Prophet Muḥammad's exposition cannot be underestimated. He is describing the single most pleasurable moment of the people of Paradise. Equally though we are reminded of the fate of those who worshipped other than God alone. It is amply clear the idol Hubal and those who worshipped him along with other false deities and their followers, are clearly distinguished from Allah and the worshippers of Allah – on this juncture Islamic tradition is very clear.[55]

In fact, a number of scholars have already noted that Hubal and Allah can't be one and the same entity. For example, over 100 years ago, Margoliouth had casted doubts on Wellhausen's identification of Hubal with Allah and dismissed it as a "hypothesis". He says:

Between Hubal, the god whose image was inside the Ka‘bah, and Allah ("the God"), of whom much will be heard, there was perhaps some connection; yet the identification of the two suggested by Wellhausen is not yet more than an hypothesis.[56]

As part of an examination as to what deity the Quraysh were supposed to have represented,[57] Patricia Crone made an argument concerning Wellhausen's suggestion that Allah might simply be another name for Hubal. Commenting on the Islamic tradition she says:

One would have to fall back on the view that Allah might simply be another name for Hubal, as Wellhausen suggested; just as the Israelites knew Yahwe as Elohim, so the Arabs knew Hubal as Allah, meaning "God". It would follow that the guardians of Hubal and Allah were identical; and since Quraysh were not guardians of Hubal, they would not be guardians of Allah, either... When ‘Abd al-Mutallib is described as having prayed to Allah while consulting Hubal's arrow, it is simply that the sources baulk at depicting the Prophet's grandfather as a genuine pagan, not that Allah and Hubal were alternative names of the same god. If Hubal and Allah had been one and the same deity, Hubal ought to have survived as an epithet of Allah, which he did not. And moreover there would not have been traditions in which people are asked to renounce the one for the other.[58]

Crone's straightforward rejection of the identification of Hubal and Allah is based on the application of common sense in view of the available evidence. Dunkin contests Crone's statement and in the process utterly confuses himself regarding her position, a direct consequence of not carefully reading the entirety of the discussion. He says, “She is not, per se, arguing against the equation of Hubal and Allah - indeed, she does not directly address the question at all.” In his speediness to form the identification of Hubal with Allah, Dunkin neglected to read on just an additional two paragraphs where he would have found the answer to his imaginary question. Crone further reinforces her position by saying,

But as has been seen, they [Quraysh] do not appear to have been guardians of Hubal, and Hubal was not identified with Allah, nor did his cult assist that of Allah in any way.[59]

Similarly, while discussing Hubal and Allah in the context of the Battle of Uhud, Hayward R. Alker points out that they both can't be one and the same.

This seems, however, unlikely, especially as, at the battle of Uhud, in the course of the warfare between Quraysh of Mecca and Muslims of Medina, the clash between the Meccans' god Hubal and the Muslims' Allah is stressed.[60]

F. E. Peters makes a clear distinction between Hubal and Allah on the basis that the former was a newcomer and the Quraysh adopted Hubal to further their political alliance with the surrounding tribe of Kinana.

Or, to put the question more directly, was Hubal rather than Allah, "Lord of the Ka‘ba"? Probably not, else the Qur'an, which makes no mention of Hubal, would certainly have mentioned the contention. Hubal was, by the Arabs' own tradition, a newcomer to both Mecca and Ka‘ba, an outsider introduced by the ambitious ‘Amr ibn Luhayy, and the tribal token around which the Quraysh later attempted to construct a federation with the surrounding Kinana, whose chief deity Hubal was. Hubal was introduced into the Ka‘ba but he never supplanted the god Allah, whose House it continued to be.[61]

Similar conclusions have been reached by von Grunebaum.

It seems quite a defensible suggestion that even before Muhammad the Ka‘ba was first and foremost the holy place of Allah and not that of the Hubal deriving from the Nabataeans and 359 other members of the astrological syncretic pantheon assembled there.[62]

What now becomes the clutching of straws for the missionaries is the tenuous claim that ʿAbd al-Muttalib's praying to Allah whilst standing next to the statue of Hubal[63] shows that "Allah to whom Muḥammad's grandfather vowed and worshiped was none other than Hubal". As to how standing next to the statue of Hubal and praying to Allah is equivalent to Hubal actually being Allah is a great mystery. By this "logic", a Christian standing next to the cross and praying to the Trinitarian deity makes him a cross-worshipper. Moreover, the text in English and Arabic clearly distinguishes and differentiates between Hubal and Allah. The Qur'an acknowledges that the Makkans were aware of Allah as one true God;[64] yet they worshipped deities other than Him who will act as intercessors.

They serve, besides Allah, things that hurt them not nor profit them, and they say: "These are our intercessors with Allah." [Qur'an 10:18]

IS HUBAL = HA-BAAL? AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL ENQUIRY

The seventeenth century witnessed a rekindled interest in Arabic studies across Western Europe. Chairs were being established in Arabic in order to facilitate the dissemination of a language whose collective scholarly output was huge and multi-disciplinary. Although the motives for establishing such endowments in England were often less conspicuous than others,[65] the primary interest in studying Arabic was religious, giving a better understanding of the biblical text and complimenting the study of Hebrew. Considered as an essential tool for the conversion of Muslims to Christianity, the Arabic language was seen as a missionizing tool with great unexplored potential.[66] The most prominent scholar of this period was undoubtedly Edward Pococke (1604–1691 CE). The son of an Anglican vicar, Pococke completed his master's degree in 1626 at Oxford, before applying himself to study the rudiments of Arabic under Matthias Pasor and William Bedwell successively. An ordained priest in 1629, he was appointed as chaplain to the English merchants in Aleppo, Syria, arriving in the city shortly thereafter in 1630. It is here Pococke received further instruction in Arabic language and literature under the guidance of the Muslim scholar Shaykh Fathallah[67] with whom he entered into an agreement with, and a servant he hired named Hamed with whom he would be able to converse in Arabic familiarly. By the time Pococke had completed his tenure some six years later, Shaykh Fathallah was reported to have said Pococke could speak Arabic as well as the mufti of Aleppo![68] With recent developments at Cambridge where a chair in Arabic had been established just a few years earlier, under the patronage of William Laud, Chancellor of the University and Bishop of London, Pococke returned to Oxford to become the first Laudian Professor of Arabic. It is here Pococke engaged in a long study of Abū'l-Faraj's (Bar Hebraeus) Al-Mukhtasar Fi’d Duwal (Compendious History Of The Dynasties), before eventually having published in 1650 a short extract under the title Specimen Historiae Arabum, a Latin translation with extensive notes on the section dealing with pre-Islamic and early Islamic history of the Arabs and Islam.[69] A landmark publication in terms of methodology and the extensive use of original sources, the books authority was recognized by western scholars who drew much from the information supplied therein. It also dispelled a number of absurd Occidental fantasies reverberating in Christendom regarding Muḥammad and Islam.[70] In his notes section dealing with the religion of jahaliya, Pococke discusses the most commonly mentioned idols such as the three "daughters of Allah", Allāt, al-ʿUzzā and Manāt. Perhaps the first to suggest so in a published work, Pococke supposed Hubal was equivalent to Hab-baal. He said,

Quàm pulchrè convenit figmento isti nomen suum, ut sit חכל Vanitas? Quòd si cum nomine suo ad Arabes transierit, erat forsan illis à quibus mutuatum sumpserunt חכעל Habbaal, vel חכל Habbel: ὁ βηλ.[71]

A testament to the fact his work remained authoritative several centuries after it had been published, the views of Pococke regarding the idol Hubal and its ultimate derivation were subsequently popularised throughout a wide range of scholarly literature in Western Europe. Hävernick's exposition of the Old Testament directed at the higher critics of Germany contained a section on the Arabic language. Briefly recounting pre-Islamic idolatry he says of the idol Hubal, “... a new Aramaic worship was introduced, instead of the ancient imageless worship, statues of idols were placed on the Kaaba; Hobal הַבּעַל, the Great Baal absolutely so called (Münter, Relig. d. Babylon. s. 18, ff.) was reverenced, ...”[72] Again, briefly surveying pre-Islamic Arabia on the eve of Islam, Muehleisen draws a comparison between Hubal and Baʿal by citing Pococke mentioning his Specimen Historiae Arabum "has not yet been surpassed".[73] In both cases the indebtedness to Pococke is evident. However, Pococke's derivation was to find its most unusual expression in the writings of the Dutch orientalist Reinhart Dozy (1820–1883 CE). His extraordinary hypothesis attributed the establishment of the sanctuary at Mecca to Davidic times by Jews from the tribe of Simeon who convened the "festival" of Makkah. As there were no prophets, priests or rabbis at Makkah who could sway the people by undermining their modes of worship, Dozy thought the original form of worship of the Jews could thus be properly discerned, the traces of which had essentially disappeared from the Old Testament. Therefore, the old Jewish religion could be inferred from the Simeonites practices at Makkah. Dozy believed the ancient religion of Israel was not the worship of Jehovah, but of Baʿal due to the fact he was worshipped by the Simeonites at Makkah in the form of Hubal meaning hab-baʿal "the Baʿal" which had been imported from Syria.[74]

From this assortment of sources the identification of Hubal with the Baʿal was thus passed into the Christian missionary literature. Contrasting the differences between the Christian conception of God and the Muslim one, Zwemer suggested Hubal was in fact none other than Allah, noting the Baal-Hubal identification made by Dozy and Pococke.[75] Zwemer terminates the discussion with some emotive imagery, "Islam is not original, not a ripe fruit, but rather a wild offshoot of foreign soil grafted on Judaism."[76] – one might say a somewhat self-defeating statement in light of Dozy's highly eccentric views. Zwemer's views have been taken up in earnest by contemporary missionaries highlighting the alleged Baʿal-Hubal-Allah worship of the Muslims. The missionaries hypothetically ask did the Makkans worship the God Yahweh? Special emphasis is placed on Dozy's Baʿal-Hubal identification, which unbeknown to the missionaries requires an implicit acceptance of his historical reconstruction on which his identification is principally grounded. The missionaries have unwittingly established pagan Baʿal worship for the Jews and themselves besides the worship of Jehovah whom Dozy discovered was idolised in the form of a he-goat.[77] Moving back to more solid ground, scholars have long since noted the fragile basis on which this identification was made,

The name [Hubal] cannot be explained from the Arabic for the etymologies in Yākūt etc. condemn themselves, but Pocock's supposition that Hubal is equivalent to הַבּעַל, although defended by Dozy, is hardly better founded.[78]

Such cautionary advice has not deterred other like minded missionaries from advancing this more than three hundred and fifty year old hypothesis. Nehls says:

Interesting is the name HUBAL (in Arabic and Hebrew script the vowels were not noted). This shows a very suspicious connection to the Hebrew HABAAL (= the Baal). As we all know this was an idol mentioned in the Bible (Num. 25:3, Hosea 9:10, Deut. 4:3, Josh. 22:17 and Ps. 106:28-29).

In fact, such an argument, albeit in a more sophisticated way, was also made by Sergio Noja.[79] Noja hypothesis can be summarized like this. Hubal consists of hbl (ھُبَل). The h- or hn- article in Ancient North Arabian was the forerunner of the ʾal- of Arabic. As for bl, it was modified with time from bʿl (بَعْل). With the loss of ʿayn in the middle of b and l, bʿl became bl. Furthermore, since ha-bʿl means "the lord", or "the god" (Baʿal was an ancient Canaanite deity) and in classical Arabic it can be written as al-bʿl which would still mean the same thing. Hubal would, therefore, be the ancient correspondent of Allah.

Noja's argument, seductive as it appears, has some serious problems. The inscriptions in the Arabian peninsula can be classified into two groups according to the form of definite article used: h- or hn- [or h(n)-] on the one hand and on the other ʾl-, the precursor of classical Arabic ʾal-.[80] Chronologically speaking, the latter group is regarded as late, since its epigraphic evidence dates only from late 1st century BCE onwards and have been found in central, north and eastern Arabia, Syria and the Negev region. The earliest occurrence of the hn- article is in the name of the goddess hn-ʾlt in the Aramaic dedications on silver bowls found at her shrine at Tell al-Mashūta, in the Nile delta.[81] These have been dated to the late 5th century BC. This dating is arrived at partly on palaeographical grounds and partly by the quite arbitrary identification of Gšm (the patronym of one of the donors), with "Geshem, the Arab" mentioned in Nehemiah (2:19; 6:1 and cf. 6:2, 6).[82] Macdonald points out that Gšm was a common name in southern Syria and northern Arabia in the pre-Islamic period and there is no external evidence to suggest that these two occurrences refer to the same person.[83] However, the ʾal- group appears to be more ancient as Herodotus stated that the Arabs worshipped a goddess name Alilat, Al-ilat (or Allat, "the goddess").[84] This tells us that this form of Arabic definite article was used as early as the 5th century BCE. However, this does not give us any idea about the dialect in which such an article was used.[85]

Attempts have been date the hn- article even earlier than ʾal- by the Christian apologist Dunkin. He claims that:

...Livingstone has proposed a reading back of the hn- form (as it would have appeared in the Arabian dialect) into certain Arab terms which were apparently carried over wholesale into the Akkadian of a triumphal inscription celebrating victories won by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (r. 744-727 BC). While this reading is more tenuous, it may well push the epigraphic evidence for the hn- form in Arabian languages back another three centuries. So, we see that the hn- form is definitely ancient.

While he admits that the reading is quite tenuous, as scholars also admit,[86] it has not dissuaded him to make the claim that the hn- form is "definitely ancient". However, a closer reading of Livingstone's article reveals something entirely different from what Dunkin is claiming. Livingstone says that:

The suggestion is made here that what has been heard is the Arabic definite article and that the above inscription is at present the earliest known attestation thereof. A spoken form han-nāqāt(u) is to be postulated....

The material discussed in this article can be placed within the context of the history and classification of the languages of Pre-Islamic Arabia.... The form discussed here could of course equally well belong to an al- language or a han- language in Beeston's classification, but would in any case push the prehistory of Arabic within that classification back a further three hundred years.[87]

Livingstone is saying that the text of inscription of Tiglathpileser III (744-727 BCE), in particular, the word a-na-qa-a-te can be considered as having an Arabic definite article ʾal-, as in an-nāqāte. In addition, he also postulates han-nāqāt(u) as the spoken form. Contrary to what Dunkin had claimed concerning the antiquity of hn- form, Livingstone says that the form of the definite article discussed by him can "equally well belong to an ʾal- language or a han- language", thus pushing them back another three centuries. Clearly, Livingstone's conclusions do not support Dunkin's claim of antiquity of hn- article only.

The idea that the h(n)- article found in Ancient North Arabian is the ancestor of Arabic ʾl- has been suggested by scholars over a long period. One of the earliest to propose this hypothesis was Wensinck.[88] His line of reasoning is this:[89] At the outset, the tribes of Northern Arabia used the article h-. This he interprets as hā-, which was gradually reduced to hă-, a consequence of this shortening being the reinforcement of the first consonant of the following word by way of compensation, for example, hā-kitāb > hă-kkitāb > han-kitāb > hal-kitāb > ʾal-kitāb. He then adds that hesitating the form han- began to shift into the cognate form hal. Gradually, however, hal- grew the usual form of the article in connection with gutturals, semi-gutturals and also with labials among various tribes. However, Wensinck's conclusion has been obtained by taking up specimens of the various types of the article to be found among the tribes of Northern Arabia and by the theoretical reconstruction of a chain of evolution. Not surprisingly, this view has come under criticism due to the lack of epigraphic evidence for showing the actual transformation of h(n)- to Arabic ʾl-.[90] Theoretically, it can be argued that it could have happened in a number of ways, the problem always come back to the lack of epigraphic evidence for the actual process.[91] Noja assumed a similar transformation from the Ancient North Arabian h- to Arabic ʾl-.[92] Not surprisingly, he did not furnish any proof either.

After claiming the alleged antiquity of hn- article, the Christian apologist Dunkin is of the opinion that /n/ in hn- can be assimilated to form ha- although this turns out to be exactly the reverse of what scholars like Wensinck have proposed. Moreover, he claims to have the support of modern scholarship for his creative opinions! Let us begin with his statements and examine them one by one.

The proposed assimilation of the n in hn-ba'al ---> haba'al is certainly possible linguistically. Southern and Vaughn demonstrate that the assimilation of an n before a consonant is fairly typical in North Semitic languages, and indeed they note that it is well-attested and not just theoretical. This same phenomenon is observed in Hebrew, for instance, where the terminal n in the preposition min (with) is assimilated with the doubling of the following consonant (except, of course, when before a guttural or a resh, in which case the prepositional vowel is lengthened along with the assimilation of the nun). Voigt further points out that old North Arabic forms show assimilation of the n to the following consonant, and do not seem to show a doubling of the consonant, as is found in some other North Semitic languages. Thus, the proposed elision by Noja is certainly possible on this count, as well.

Southern and Vaughn have indeed demonstrated that the assimilation of an /n/ before a consonant, i.e., nC > CC, is typical in the North Semitic languages.[93] They have also shown that the phonetic character of /n/ in North Semitic languages fosters this assimilation and is accompanied by doubling of the consonant following /n/. It is hard to imagine how this is going to support the conversion of hn-baʿal to form habaʿal. The actual outcome of assimilation of /n/ to the following consonant with its doubling would result in hn-baʿal becoming hab-baʿal. This is certainly not the outcome which Dunkin expected. Furthermore, Dunkin claims that according to Voigt (on p. 225), the old North Arabic forms show assimilation of the /n/ to the following consonant, without doubling of the consonant itself.[94] There is no such claim by Voigt. In fact, he says:

See also hn-qbr, 'the tomb', next to h-qbr.[95]

What Voigt points out is the well-known case of Lihyanite inscriptions where hn- and h- forms exist side by side. Such a close co-existence of h(n)- articles in Lihyanite inscriptions has been a source of curiosity as well as extensive scholarly studies for more than 100 years.[96] Dunkin's case of alleged conversion from hn-baʿal or habaʿal by assimilation of /n/ has now fallen apart. However, an important point needs to be made. In the discussions by scholars concerning the fate of the consonant next to the article h(n)-, it is always noted that whether or not there is assimilation of consonant by doubling (or without one), the character of h- or hn- still remains the same, i.e., they still function as definite articles. In other words, hn-baʿal or hab-baʿal would mean "the Baʿal". The noun here is not going to transform into something different such as "Hubaʿal".

With the alleged assimilation of /n/ in hn- article sorted out, let us now move to the name bʿl to become bl with the loss of ʿayn. For such a process to happen bʿl would have to have been transmitted through a language such as Akkadian or Punic in which the ʿayn had disappeared. This would give in Akkadian Bel and in Punic Bol. Both forms were present at Palmyra, but Palmyrene does not use the Ancient North Arabian definite article h- or hn-. Since the word bʿl, with the ʿayn, exists in Arabic as a common noun, and as the name of a pre-Islamic idol, it would be very difficult to argue that Arabic had received the word or name by this route, let alone why it had been given an Ancient North Arabian definite article. Such an enormous difficulty has not deterred Dunkin to make some more foolish claims. He says:

However, the dropping of the ayin is not impossible. Drijvers certainly did not consider it so, as he saw no difficulties in stating that Ba'al-Bel-Bol (together) was the original West Semitic form of the name. Beeston states that the "conversion of consonant into vowel" such as occurs in the Punic bol for ba'l, is "well-attested in Semitic languages". More to the point, Voigt demonstrates that glottal stops in Arabian dialects can contract, using the example of the contraction of the hamza in the conversion bi-?al ---> bi-l. This same principle could certainly apply to the contraction of the similar ayin. As such, Noja's argument, based as it is upon the disappearance of the ayin, is most certainly plausible...

....

Nobody has proposed that the name Hubal came from Palmyrene, and there were certainly many other dialects, including those much closer to the Arab milieu such as Nabataean (in which the name appears as hblw) from which an entrance by Hubal into the Arab consciousness could have been made. Many of these dialects also used the ha/hn- form of the article.

It is hard to see how the statements of Drijvers and Beeston are in contrary to what we have stated concerning dropping of ʿayn in bʿl in Akkadian or Punic. Moreover, Dunkin himself rejects the notion that the name Hubal came from Palmyra and considers it to be a Nabataean deity. One now wonders why he is invoking the dropping of ʿayn in languages other than Nabataean itself! It must be emphasized that in both Nabataean and Safaitic inscriptions a deity called Baʿalshamin is always written as bʿlšmn, i.e., with an ʿayn between b and l. There is no Nabataean and Safaitic epigraphic evidence which shows the name bʿl becoming bl with the loss of ʿayn, which in turn enabled hbʿl to become hbl. As mentioned earlier the word bʿl, with the ʿayn, exists in Arabic as a common noun and it is also found in Surah al-Saffat in the Qur'an[97]

"Will ye call upon Ba‘al (b‘l) and forsake the Best of Creators" [Qur'an 37:125]

The Qur'an condemns Baʿal worship. Moreover, it is also clear that in both the Nabataean and Arabic scripts the difference between Hubal and Baʿal (with an ʿayn) always existed, and that they were considered two distinct deities. Furthermore, Dunkin claims that Voigt had demonstrated (p. 225) "that glottal stops in Arabian dialects can contract" and he uses the example of "the contraction of the hamza in the conversion bi-?al ---> bi-l". Dunkin then makes an even more surprising claim that such a principle "could certainly apply to the contraction of the similar ayin". A closer look at Voigt's paper give us a completely different picture from Dunkin's strange claims. Voigt says:

Some Arab grammarians argued that the short form of the article went on to form hamza. After vocal would be an elision of the hamza and the contraction of the adjacent vowels, so for example *bi-’al-> bi-l-.[98]

Voigt has not "demonstrated" that the "glottal stops in Arabian dialects can contract". Rather he points out that some Arab grammarians consider the short form of the article ʾl- went on to form hamza or to be precise hamza al-waṣl, the glottal stop of the juncture. This is not the place to discuss the subject present in elementary Arabic grammar books, but it is worthwhile adding that hamza al-waṣl is a phonetic device affixed in the beginning of a word for ease of pronunciation and is accompanied by a vowel /i/, /u/ or /a/.[99] In the example, bi-ʾal-, where the article ʾal- is in non-sentence-initial position, the hamza and its short vowel /a/ on the definite article are deleted, although the alif seat remains in the spelling. This makes bi-ʾal- read as bi-l-. Similar examples include wa-ʾal-which is read as wa-l-. Being a phonetic device to aid pronunciation, hamza al-waṣl has nothing to do with contraction of consonants and most certainly could not be applied to the "contraction of the similar ayin". The case of Dunkin for "contraction" of ʿayn to support the conversion of bʿl to bl has now completely collapsed.

With the stripping away of the chaff that surrounds the kernel, we are now left with some mopping up. One of the issues is dropping of the ʿayn in the area where h(n)- dialects were present. Dunkin claims that his

... historical reconstruction is supported by the fact that the name for this god was "Hubal", without the ayin. This would seem to indicate that his origin was from among a dialect group which used the bl-form, and which also used the ha/hn- article. Dialects like these found representation in the northern Hijaz and Syrian areas. Further, this introduction appears to have taken place prior to the establishment of the ’l-form (whose most well-known representative is the Classical Arabic of the Qur'an and the other traditional writings) as the dominant dialect type (around the beginning of the 6th century AD), which is why we would not see Noja's hypothetical ’l-bal form.

We are not told as to which "dialect group" uses the bl-form as well as the h(n)- article which resulted in the formation of the name "Hubal". It is safe to assume that he himself does not know what this "dialect group" is. But it is good to make matters clearer in this regard. The h(n)- dialects are all classified under Ancient North Arabian[100] and they always had ʿayn as one of the consonants.[101] As for the bl-forms, as opposed to bʿl as in Ancient North Arabian, they come from those dialects where ʿayn had disappeared such as Akkadian (Bol) and Punic (Bel). Both these forms were present at Palmyra, but Palmyrene does not use the Ancient North Arabian definite article h(n)-. In other words, the "dialect group" which Dunkin claimed to have used h(n)- article as well as bl-form is his own inventions; it simply does not exist. Therefore, there are two opposing choices before Dunkin:

Dunkin claimed that his unknown, unnamed, and now clearly fictitious "dialect group" which alleged to have used both h(n)- article as well as bl-form, was introduced prior to the establishment of the ʾl-form as the dominant dialect around c. 6th century CE. This is rather strange. The most obvious characteristic of what is called the "Old Arabic" by scholars, is the use of the definite article ʾl-. The earliest document which is indisputably in Old Arabic written in the musnad script, was found at Qaryat al-Faw dated to the first century BCE. This text uses the article ʾl-, the *banā, rather than *banaya, the ʾfʿl form of the causative stem, and the preposition mn rather than bn.[102] In fact, there are numerous inscriptions dated before the advent of Islam which contain the ʾl- article. Undoubtedly, Dunkin's attempts to find this fictitious "dialect group" are starting to resemble the case of clutching the straws.

In the light of archaeological evidence, Noja's and the Christian missionaries' hypothesis that Ha-Baʿal ("the Lord") became Hubal now becomes completely untenable, let alone Hubal being Allah! There is nothing in the missionary hyperbole that "seriously damages the Muslim claim regarding Allah in pre-Islamic times being the same God of Abraham".

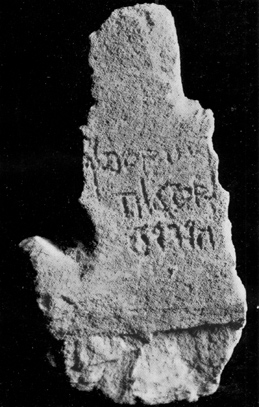

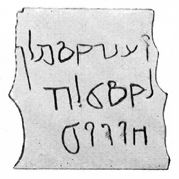

The pre-Islamic god Hubal, whose name is known from early Arabian sources, was also known apparently to the Nabataeans. Hubal in a Nabataean inscription dated to c. 1 BCE / CE from Mada'in Salih (Hijr or Hegra, Figure 1), north-west of Madinah, appears as hblw. The final -w is typical of Nabataean divine and personal names.

Figure 1: Nabataeans and their trade routes.[103]

The inscription is funerary in character and Hubal's name appears with Dushara and Manōtu (i.e., Manat). The inscription reads:

... p’yty ‘mh ldwšr’ whblw wamnwtw šmdym 5 ...

... [he] shall be liable to Dushara and Hubalu and Manotu in the sum of 5 shamads ...[104]

Despite Hawting's misgivings,[105] there is no doubt about this reading.[106] Another possible occurrence of the name Hubal is in the Nabataean inscription (dated 48 CE) from Pozzuoli near Naples.[107] The reading of J. T. Milik was reported by Starcky, although some doubt remains.[108] The name appears as bnhbl, without the final -w and therefore an exact correspondent of the Arabic form. It was interpreted by Starcky as "son of Hubal".[109] But it can also be interpreted as "Hubal has fashioned".[110] Interestingly, bnhbl also appears in a "Thamudic" inscription from Northern Arabia.[111] Milik and Starcky reported that the name Hubal also appears in a personal name, brhbl, "Son of Hubal", in a dedicatory text dated to 25 BCE.[112] The authors Milik and Starcky regarded it as an Aramaic version of the name found in the Pozzuoli inscription. Based on the epigraphic evidence, Healey says that the cult of Hubal was restricted in Nabataean inscriptions to Hegra. Therefore, Hubal can be considered as a local god and his cult did not spread at all among the Nabataean élite, despite its Arabian origins.[113]

Was Hubal a Moon-god? The information that we have concerning the nature of Hubal comes from only two sources: Islamic and Nabataean. They do not say, nor do they suggest, that Hubal was a Moon-god. In spite of lack of any evidence of lunar connotations of Hubal, it has not deterred scholars to claim that Hubal was a Moon-god. The claim of Christian missionaries that Hubal was a Moon-god is based on a citation from Mahmoud Ayoub's Islam: Faith And History.[114] A similar claim was also made by Robert Morey.[115] In fact, the claim that Hubal was a Moon-god is rather old. More than 100 years ago Hugo Winckler suggested there was a Moon-god cult in Makkah and that Hubal was a Moon-god[116] and it was subsequently repeated by Carl Brockelmann.[117] Gonzague Ryckmans tentatively associated Hubal with the Moon.[118] Such ideas were the result of the scholarship of Ditlef Nielsen who claimed that all ancient Arabian religion was a primitive religion of nomads, whose objects of worship were exclusively a triad of the Father-Moon, Mother-Sun and the Son-Venus star envisaged as their child.[119] Not only was this an over-simplified view based on an unproven hypothesis, it is also quite absurd to think that over a millennium-long period during which paganism is known to have flourished, there was not substantial shifts of thinking about the deities. As noted earlier, Nielsen's triadic hypothesis was handed incisive rejoinders by many scholars. With regard to those who connect Hubal to the Moon, Brown points out such a connection is not based on any evidence and is merely inferred by astral analogy. He says:

Ryckmans, Les Noms, p. 9, tentatively associates Hubal with the moon, but there is no necessary evidence for this association in the name, and it can only be inferred in order to supply the Hijazi pantheon with a moon-deity, which on analogy with other pantheons it is supposed it must have had.[120]

Even the foundation of such an analogy is faulty as it is based solely on the acceptance of Nielsen's now discredited triadic hypothesis. Acknowledging the "generally received opinion" of Nielsen regarding the worship of astral triads in ancient South Arabia, Brown notes there is no such indication of a fixed schematisation in Central / North Arabia. There are a bewildering array of deities whose precise nature and function is extremely difficult to define. For instance, an examination of the theophorous names reveals the presence of Jupiter (t-m-ʿ-h-w-r, "devotee of ʿAhwar (Jupiter)".[121] Brown proposes a number of connections to other stars and planets as well. For example, he suggests the idol/deity Su’ayr, a tall rock connected with the Malik, Milkan and Banu Bakr of Kinanah, was associated with the stars as a number of stars bore this name.[122]

Despite the lack of any evidence, it is somewhat surprising to learn therefore that the Christian apologist Dunkin purports to have seen evidence which proves Hubal had "specifically lunar, characteristics". In an attempt to prove Hubal was a Moon-god, Dunkin erroneously summarises the Encyclopaedia Of Islam (New Edition). It must be stated at the outset neither the first nor new edition of the Encyclopaedia Of Islam suggests anywhere that Hubal was a Moon-god, let alone Hubal being Allah.[123] Fahd points out Hubal's most characteristic role in the Kaʿbah was that of a cleromantic (divination by lots) divinity,[124] something which the missionary excludes mentioning and for good reason. Allah had never been worshipped as a cleromantic divinity by the earliest Muslims; on the contrary, the Qur'an categorically forbids divination (e.g., 5:3, 5:90) and describes it as the handiwork of Satan. In order to decisively prove Hubal was a Moon-god, the apologist makes use of a book called The Joy Of Sects, authored by jazz critic and reviewer Peter Occhiogrosso, better known for his publications co-authored/written with Frank Zappa and Larry King. Should one transform a music journalist (to say nothing of Occhiogrosso) into a specialist on the nature of the deities worshipped in seventh century Arabia at the advent of Islam? Such a bizarre use of sources is astonishing and calls for an explanation.[125]

Clearly, there is no evidence of a connection between Hubal and the moon. Those scholars who have made a connection between Hubal and the moon have rested their case on flimsy evidence. Not surprisingly, Winckler's claim that Hubal was a Moon-god was refuted by Fahd.[126] While dealing with the Nabataean deity Hubal, Healey agrees with Fahd's view while pointing out the age-old assumption of Nielsen that all Arabian religion was ultimately astral. He says:

On the other hand Fahd rightly rejects the attempts by some earlier scholars to connect Hubal with Saturn or the moon... Such suggestions have been based partly on the assumption that all Arabian religion is ultimately astral and partly on the Islamic inheritance of a lunar calendar...[127]

The claim of Hubal being a Moon-god rests on no evidence and is inferred by astral analogy based on Nielsen's hypothesis, which Dunkin himself has rejected. Clearly, the apologist can't have his cake and eat it too. Let us now move on to his attempts on connecting Hubal with Allah with more fabricated evidence.

WHAT IS IN A NAME? HUBAL, ALLAH & PRE-ISLAMIC CHRISTIANITY

Given that Dunkin's construction of Hubal from the h(n)- article and bl-form turned out to be spurious and shown to be banked heavily on misquoting modern scholarship, let us not turn our attention to some of the desperate attempts to connect Hubal with Allah. In this effort, Dunkin says: