![]()

On The Use Of Miṣr In The Qur'ān

Islamic Awareness

© Islamic Awareness, All Rights Reserved.

First Composed: 22nd June 2012

Last Updated: 20th November 2012

| Tweet |

|

|

|

Assalamu-ʿalaykum wa rahamatullahi wa barakatuhu:

One of the most interesting aspects of the Qur’an is that it is universal in both its themes and contexts. It relates the story of mankind beginning with creation itself, navigating through various landmarks of human existence, not bound by any particular time, border or location. This unique aspect of the Qur’an is reflected in the paucity of the mention of names of places. One place which is mentioned more than any other is Egypt, referred to as miṣr in the Qur’an. It is mentioned 4 times,[1] twice in the story of Prophet Yusuf (Qur’an 12:21 and 12:99) and twice in the narrative dealing with Prophet Moses (Qur’an 2:61, 10:87 and 12:21). However, in the case of Qur’an 2:61, instead of miṣr, the word miṣran is used which means ‘town, city, dwelling’. The Arabic-English Dictionary Of Qur’anic Usage provides the usage of miṣr in the Qur’an. It says:

م / ص / ر m-ṣ-r to milk with the tips of the fingers; to separate; to give sparsely; place where horses are trained; boundaries, city, to urbanise; Egypt; reddish clay; intestines. Of this root, only مصر miṣr occurs fives times in the Qur'an.

مصر miṣr 1 [n.] city, town urban dwelling (2:61) اهْبِطُوا مِصْرًا فَإِنَّ لَكُم مَّا سَأَلْتُمْ go into a town and there you will find what you have asked for 2 [proper name] Egypt (43:51) أَلَيْسَ لِي مُلْكُ مِصْ is the Kingdom of Egypt not mine?[2]

As for the meaning ‘Egypt’, let us consider the following examples from the Qur’an.

Later, when they presented themselves before Joseph, he drew his parents to him– he said, ‘Welcome to Egypt: you will all be safe here, God willing’ [Qur’an 12:99]

Pharaoh proclaimed to his people, ‘My people, is the Kingdom of Egypt not mine? And these rivers that flow at my feet, are they not mine? Do you not see? [Qur’an 43:51]

While Joseph was a foreigner in Egypt, presumably from the land of Canaan, and Pharaoh, on the other hand, a native of Egypt, they both referred to Egypt as miṣr. A valid question may be asked as to whether Egypt during the time of Joseph and Moses was indeed called miṣr by foreigners as well as rulers of Egypt. This question can be answered by studying the diplomatic correspondences between ancient Egypt and its neighbouring states.

2. The Name ‘Egypt’ In Ancient Diplomatic Correspondence

Although Egypt had a written tradition as ancient as that of Mesopotamia, the correspondence of the Egyptian court, both for its international affairs and with its vassals, was conducted not in the language of the Egyptian Empire, but in the Akkadian language (i.e., Babylonian) and in the Akkadian cuneiform script. Moreover, it may be assumed that due to the esoteric character of the Egyptian script and linguistic culture, the internal correspondence of the Egyptian empire with other powers and vassals was not written in its language.[3] In the 14th century BCE, Akkadian had acquired the status of lingua franca by which kings reigning all over the Near East were able to communicate. The most important diplomatic correspondence in the Akkadian cuneiform script comes from the corpus called the Amarna Tablets or Amarna Letters.[4] The Amarna letters are named after the site in central Egypt where they were discovered: Tell al-Amarna, or ancient Akhetaten, was the city chosen by Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV). The relations between Egypt and the other great powers of the ancient Near East occupy a central place in the Amarna Letters. The principal powers, as depicted in Figure 1, were Babylon (EA 1-14), Assyria (EA 15-16), Mitanni (EA 17, 19-30), Arzawa (EA 31-32), Alashia (EA 33-40), and Hittites (EA 41-44).[5] Furthermore, the corpus includes not only letters but also some material of use to Egyptian students learning Akkadian. Moving on to dating, from the internal evidence we can observe a terminus post quem in the 30th regnal year of Amenhotep III (1390-1353 BCE) with a terminus ante quem the desertion of the city of Amarna, commonly believed to have happened in the first year of the reign of Tutankhamun later in the same century in 1332 BCE.[6]

Figure 1: Map of the ancient Near East c. 1400 BCE.

The other important source of information is the Hittite diplomatic correspondences, again written in the Akkadian cuneiform script, involving the Hittite and Egyptian royal families.[7] The evidence of what Egypt was called in Akkadian can be divided into two: Firstly, what Egyptians called their country, and secondly, what other neighbouring states called Egypt, in their respective diplomatic correspondences.

DIPLOMATIC CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN ANCIENT EGYPT AND NEIGHBOURING STATES

As is common for correspondence in most cultures, Amarna letter-writing was formulaic. In general, the kings called each other by proper names and expressed their equal political status by the addressing formula “Say to X1. king of Y1... thus says X2, king of Y2...”. They also used the denomination “brother” (i.e., a king of equal rank),[8] and by employing the same words for greeting. Some kings were entitled to be called “great king,” that is a king who was a suzerain of vassal states and was equal in his political status to the other great powers. It goes without saying that obsequiousness is conventional for ordinary people making requests. As for the Amarna scribes, they inherited, and sometimes adapted, conventions of correspondence derived from Mesopotamia.

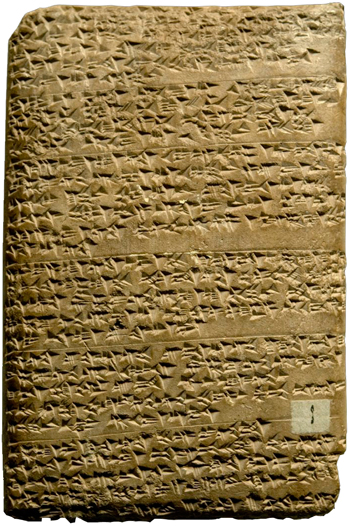

One of the earliest correspondences in the Amarna letters took place between Amenhotep III (1390-1353 BCE), a ruler of ancient Egypt from the New Kingdom Period and Kadašrman-Enlil I (1364-1350 BCE),[9] the king of Karaduniaš (or Babylonia). The cuneiform inscription sent by Amenhotep III to Kadašrman-Enlil I begins by saying:

EA 1 (=L 29784, BB 1, W1, Kn 1)

Transcription: [a-na]m ka-[da]-áš-ma-an-dEnlil šàr mâtka-ra-ddu-n[i-i]á-a[š] aḫi-ia ki-bí-ma um-ma mNi-ib-mu-a-ri-a šarru rabû šàr mâtmi-iṣ-ri-iki aḫu-ka-ma a-na maḫ-ri-ia šul-mu a-na maḫ-ri-ka lu-ú šul-mu a-na bîti-ka a-na aššâti-ka a-na mârê-ka a-na amêlûtrabuti-ka sise-ka isnarkabâti-ka a-na libbibi mâtâti-ka da-an-ni-iš lu-ú šul-mu a-na ia-a-ši šul-mu a-na.[10]

Translation: Say [to] Kadašrman-Enlil, the king of Karadun[i]še, my brother: Thus Nibmuarea, Great King, the king of Egypt, your brother. For me all goes well. For you may all go well. For your household, for your wives, for your sons, for your magnates, your horses, your chariots, for your countries, may all go very well.[11]

Here the ‘throne name’ (or prenomen) of Amenhotep III was used. In the cuneiform inscriptions, Nub-maʿt-reʿ (‘Lord of the Truth is Reʿ’),[12] the prenomen of Amenhotep III, was rendered as Nibmuarea, and in some cases with emendation to wa also read as Nimuwaria.[13] It is interesting to note that ‘Egypt’ was called mi-iṣ-ri-i in the royal correspondence of Amenhotep III.

Our next example is a royal correspondence between Amenhotep III, the ruler of ancient Egypt and Tarḫundaradu, the king of Arzawa.

EA 31 (=C 4741, WA 10, Götze VB, Kn 31)

Transcription: [u]m-ma mNi-mu-ut-r[i-i]a šarru rabû šàr mâtumi-iṣ-ṣa-ri [a]-na mTar-ḫu-un-da-ra-bab šàr mâtAr-za-wa ki-bí-ma kat-ti-mi Sìg.In Bit. Zun-mi Dam.Meš-mi Tur.Meš-mi amel mešGal. Galaš Zab. Meš-mi ImêrKúr.Ra.Zun-mi bi-ib-bi-id-mi Kúr. Kúr. Zun-mi-kán an-da ḫu-u-ma-an Sìg.In...[14]

Translation: Nimuwa(r)eya, Great King, king of Egypt, (speaks) as follows: Say to Tarḫundaradu, the king of Arzawa: By me all is well. For my houses, my wives, my children, my magnates, my troops, my chariot-fighters all my property in my countries, all is well. By you (too) may all be well...[15]

As mentioned earlier, ‘Nimuwaria’ was, of course, recognised as the cuneiform rendering of the throne name of Amenophis III. Again, we notice that ‘Egypt’ was called mi-iṣ-ṣa-ri, a variant of mi-iṣ-ri-i, in the royal cuneiform inscriptions from ancient Egypt.

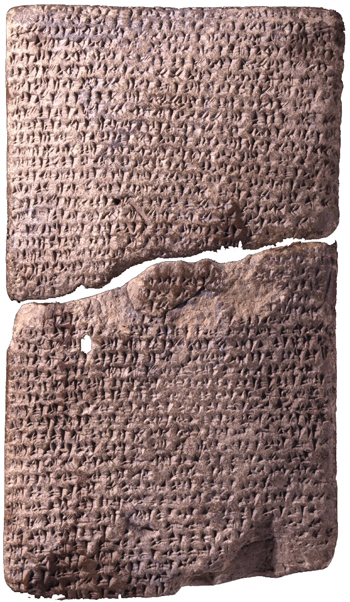

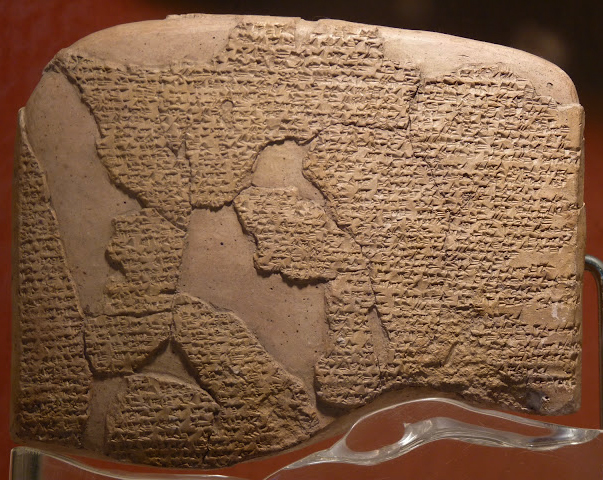

We now turn to our last example – one of the most famous examples of a peace treaty – between Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) and Ḫattušili III, king of Ḫatti, concluded in or around 1259 BCE. In this treaty, Ramesses II refers to himself as rabû šar matMi-iṣ-ri-i , i.e., the ‘king of Egypt’. This treaty was the first known diplomatic agreement from the Near East, and it is the oldest written treaty that still survives today. A copy of this treaty is prominently displayed on a wall at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. The interesting part of this treaty was that it was recorded, both in Egypt where it was inscribed on the walls of temples in hieroglyphics, and in the former Hittite empire - present day Turkey - where it was preserved in cuneiform script on baked clay tablets. The two versions agree substantially in content, and there is a close correspondence in the phraseology. It is the treaty in the cuneiform script that is of interest to us. We are providing only a small part of the text of the peace treaty which is relevant to this article.

KBo I, 7 and 25

[Ri-a-ma-še-ša ma-a-i] iluA-ma-na šarru rabû šar matMi-iṣ-ri-i ķarradu i-na gab-bi mātāti mār-[šu ša] [Mi-in-]mu-a-ri-a šarri rabî šar matMi-iṣ-ri-i ķarradi-i mār māri-šu ša Mi-in-paḫi-ri-ta-ri-a šarri rabî [šar matMi-iṣ-]ri-i ķarradi a-na Ḫa-at-tu-ši-li šarri rabî šar matḪa-at-ti ķarradi mār Mur-ši-li šarri rabî [šar matḪa-at-ti] ķarradi mār māri-šu ša Šu-ub-bi-lu-li-ú-ma šarri rabî šar matḪa-at-ti ķarradi a-mur a-nu-ma at-ta-din [aḫu-ut-ta damiķ]ta sa-la-ma damķa i-na be-ri-in-ni a-di da-ri-ti a-na na-da-ni sa-lama damķa aḫ-ḫu-ta damiķta [i-na rik-si] matMi-iṣ-ri-i ka-du matḪa-at-ti a-di da-a-ri-ti ki-a-am.

[Riamašeša-mai]-Amana, the great king, king of Egypt, the strong in all lands, son [of] Minmuaria, the great king, king of Egypt, the strong, son of the son of Minpaḫiritaria, the great king, [king of Egy]pt, the strong, unto Ḫattušili, the great king, king of the land Ḫatti, the strong, the son of Muršili, the great king, king of the land Ḫatti, the strong, son of the son of Šubbiluliuma, the great king, king of the land Ḫatti, the strong, behold now I give [good] brotherhood, good peace between us forever, in order to give good peace, good brotherhood by means of [a treaty (?)] of Egypt with Ḫatti forever. So it is.[16]

A comment needs to be made concerning the names of ancient Egyptian rulers rendered in the cuneiform inscriptions. Ramesses II, whose nomen is Ramesses Meryamun, is written as ‘Riamašeša Maiamana’. On the other hand, pronomen (or ‘throne name’) is used for Ramesses II’s father Seti I (Minmuaria = Menmaʾtreʿ) and grandfather Ramesses I (Minpahiritaria = Menpehtyreʿ).[17]

DIPLOMATIC CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN NEIGHBOURING STATES AND ANCIENT EGYPT

In the earlier section, we dealt with the examples of diplomatic correspondence originating from ancient Egypt to the neighbouring states. It was seen that ‘Egypt’ was called mi-iṣ-ri-i (or mi-iṣ-ṣa-ri-i, a variant) in the royal cuneiform inscriptions. In this section, we will show examples of royal correspondences originating from neighbouring states to Egypt. Our first example is that of Aššuruballit (1353-1318 BCE),[18] king of Assyria writing to the Egyptian ruler Napḫu'rureya. ‘Napḫu'rureya’ is none other than Akhenaton (1353-1356 BCE), also known as Amenhotep IV, a ruler of ancient Egypt from the New Kingdom Period, whose ‘throne name’ (or prenomen) was Nefer-kheperu-reʿ (‘Beautiful are the manifestations of Reʿ’).[19] In the cuneiform inscriptions, Nefer-kheperu-reʿ is rendered as Napḫu'rureya.

EA 16 (=C 4746, WA 9, W 15, Kn 16)

Transcription: a-na mN[a-a]p-ḫu-[r]i-i.... [šarri rabi] šàr mâtmi-iṣ-ṣa-ri-i a[ḫ]i-ia k[i-bí-ma] um-ma m dA-šur-uballit šàrmâ[t] d[Aš-šu]r šarru rabû aḫu-ka-ma a-na k[a]-a-[š]á a-na bîti-ka ù mati-ka lu š[ul]-mu.[20]

Translation: S[ay] to N[a]pḫu'[r]ureya..., [the Great King], king of Egypt, my brorher: Thus Aššur-uballit, king of [Assy]ria, Great King, your brother. For you, your household and your country may all go well.[21]

Here, ‘Egypt’ is called mi-iṣ-ṣa-ri-i.

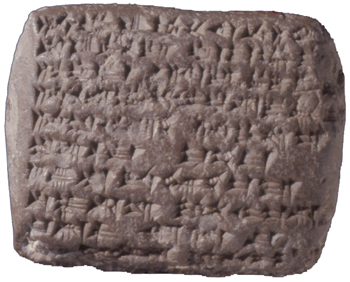

In the previous section, we saw the royal correspondence from Amenhotep III to Kadašrman-Enlil I, king of Karaduniaš (or Babylonia). Here latter's successor Burna-Buriyaš (1349-1323 BCE),[22] wrote to Napḫu'rureya, i.e., Akhenaton (= Amenhotep IV), king of Egypt (=mi-iṣ-ri-i)

EA 8 (=B 152, WA 8, W II, Schr 5, Kn 8)

Transcription: [a-na] Na-ap-ḫu-'-ru-ri[-ia] šar mâtmi-iṣ-ri-i aḫi-ia k[i-bí-ma] um-ma Bur-ra-bu-ri-ia-áš šàr mâtKa-ra[-du-ni-ia-áš] aḫ-u-ka-ma a-na ia-a-ši šú-ul-mu a-na ka-šá mâti-ka bîti-ka aššâti-ka mârê-ka amelrabûti-ka sisê-ka isnarkabâti-ka da-an-ni-iš lu šu-ul-mu.[23]

Translation: Sa[y to] Napḫu'rure[ya], the king of Egypt, my brother: Thus Burra-Buriyaš, the king of Kara[duniyaš], your brother. For me all goes well. For you, your country, your household, your wives, yo[ur] sons, your magnates, your horses, your chariots, may all go very well.[24]

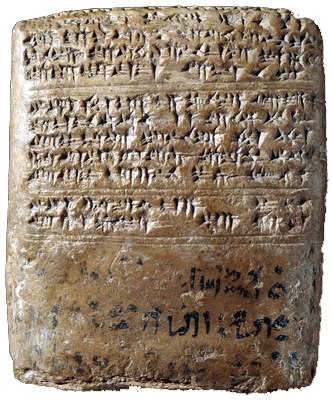

Our next example is a letter addressed to Amenhotep III from Tušhratta, king of Mitanni [Figure 1 for map]. The letter, just like other letters, starts with greetings to various members of the royal house including Tushratta’s daughter Tadu-Ḫeba, who had become one of Amenhotep’s brides. Diplomatic marriages were the standard way in which countries formed alliances with Egypt.[25] Three lines of hieratic(?) Egyptian writing in black ink, have been added, presumably when the letter arrived in Egypt. The addition includes the date ‘Year 36’ of the king. Notice that ‘Egypt’ was called mi-iṣ-ri-i in the royal correspondence to Amenhotep III.

EA 23 (=L 29793, BB 10, W 20, Kn 23)

Transcription: a-na mNi-im-mu-ri-ia šàr mâtmi-iṣ-ri-i aḫi-ia ḫa-ta-ni-ia šá a-ra-’a-a-mu ù šá i-ra-’a-a-ma-an-ni ki-bí-ma um-ma mDu-uš-rat-ta šàr Mi-i-ta-a-ni šá i-ra-’a-a-mu-ka e-mu-ka-ma a-na ia-ši šul-mu a-na ka-a-šá lu-ú šul-mu a-na bîti-ka a-na amelitTa-a-tum-ḫe-pa mârti-ia a-na aššâti-ka šá ta-ra-’a-a-mu lu-u šul-mu.[26]

Translation: Say to Nimmureya, the king of Egypt, my brother, my son-in-law, whom I love and who loves me: Thus Tušratta, the king of Mittani, who loves you, your father-in-law. For me all goes well. For you may all go well. For your household, for Tadu-Ḫeba, my daughter, your wife, whom you love, may all go well.[27]

The next example is the correspondence from the king of Alashiya, a place now identified as Cyprus,[28] to the king of Egypt (mi-iṣ-ri-i). The names of both the rulers are seldom mentioned in the Amarna Letters. A number of the Amarna letters are from the king or ministers of Alashiya. These documents are mostly concerned about the amount of copper that has been sent from Alashiya and requests for silver or ivory in return.[29]

EA xx (=B 1654, WA 15, W 30, Schr 13, Kn 33)

Transcription: a-na šarri mâtmi-iṣ-ri-i aḫi-ia um-ma šàr matA-la-ša-ia aḫu-ka a-na ia-ši šul-mu a-na maḫ-ri-ka lu-ú šul a-na bîti-ka a-na aššâti-qa mâri-ka sisî-ka isnarkabâ ti-ka ù a-na libbibi mâti-ka [da]nniš lu šul-mu.[30]

Translation: To the king of Egypt, my brother, say. Thus saith the king of Alašia, thy brother: With me it is well. May it be well with thee. With thy house, thy wife, thy son, thy horse, thy chariot, and in thy land may it be very well.[31]

Our last example is what may be described as an ancient ‘passport’. In the cuneiform inscription below, “brother” is the Egyprian king, and the “king” is almost certainly Tušhratta, the ruler of Mittani,[32] who is addressing the kings of Canaan. Strictly speaking, it is not a correspondence between the ruler of Mittani and the ruler of Egypt. Nevertheless, it gives a good idea as to how other states communicated with each other on the issues related to Egypt. Notice the repeated use of mi-iṣ-ri-i for ‘Egypt’.

EA 30 (=L 29841, BB 58, W 14, Kn 30)

Transcription: a-na šarrani šá matKi-na-a-aḫ[ḫi] ardani aḫi-ia um-ma šarru-m[a] a-nu-um-ma mA-ki-ia amêlmâr šipri-ia a-na muḫḫ šàr mâtmi-iṣ-ri-i aḫi-ia a-na du-ul-lu-ḫi a-na gal-li-e al-ta-par-šu ma-am-ma lu-ú la i-na-aḫ-ḫi-iṣ-zu na-as-ri-iš i-na mâtmi-iṣ-ri-i šú-ri-pa ù a-na qât [ame]lḫal-z[u]-uḫ-li ša mâtmi-iṣ-ri-i it-t[i] ḫa-mut-ta l[i]-il-t[e-g]uʿ ù kât-zu mi-im-ma i-na muḫḫiḫi-šu lu-ú la ib-pa-aš-ši.[33]

Translation: To the kings of Canaan, servants of my brother: Thus the king. I herewith send Akiya, my messenger, to posthaste to the king of Egypt, my brother. No one is to hold him up. Provide him with safe entry into Egypt and hand (him) over to the fortress commander of Egypt. Let (him] go on immedlately, and as far as his pre(sents) are concerned, he is to owe nothing.[34]

To summarize, our study has elucidated the fact that ‘Egypt’ was called mi-iṣ-ri-i as late as 14th century BCE as evidenced from the Amarna Tablets. Furthermore, it was seen that this usage was very widespread over a large geographical area. How early in history does this usage go back to?

ANTIQUITY OF MṢR AS THE NAME FOR ‘EGYPT’

It must be added that oldest name of ‘Egypt’ was kmt - the ‘Black Land’. This is what the ancient inhabitants of the Nile valley and delta called the first nation-state of antiquity. Ancient Egyptians referred to themselves as kmtjw which literally means ‘black people’.[35] As for miṣr being the other name of ‘Egypt’, its antiquity is difficult to determine. However, from the evidence that we have seen so far, it can be said with certainty that it goes back earlier than 14th century BCE. Commenting on the origin of name miṣr in the Qur’an, Arthur Jeffery says that it has been recognized as a foreign name by some exegetes, in particular Baidawi, “who derives it from مصرايم, which obviously is intended to represent the Heb. מצרים.”[36] He goes on to add that epigraphic south Arabian “was doubtless the source of the Qur’ānic form”. However, Jeffery also leaves a tantalizing note saying “but see Zimmern, Akkad. Fremdw. 91”. It is this note which is of great interest to us for the understanding of the antiquity of the word miṣr.

akk. miṣru Grenze, Gebiet (viell. m-Bildung von eṣēru St. jṣr, einritzen, zeichnen) : > aram. miṣra, meṣrā (> arab. miṣr). - Viell. stammt auch der Name für Ägypten, hebr. Miṣrajim, aram. Meṣrēn, arab. Miṣr, akk. Miṣri, später Miṣir, Muṣur, erst von jenem miṣru Grenze, und bedeutet also eigentlich : Mark.[37]

Zimmern states that Arabic miṣr being the name of ‘Egypt’ originated from Akkadian miṣru via Aramaic. Notice that Akkadian miṣru also means ‘border area’ – the Arabic usage of miṣr is consistent with Akkadian as well.[38] According to The Assyrian Dictionary, from the extant cuneiform evidence, this usage goes back to the Old Babylonian Period (1950–1530 BCE).[39] Although this answers (partly!) the issue of antiquity of miṣr, one may ask the question as to what is the origin of miṣr for Egypt. It must be added that the name ‘Egypt’ is the modern version of ‘Aigyptos’ (=Αίγυπτος), the Greek word derived from the Egyptian for the city of Memphis – Ḥet-Ka-Ptaḥ (or Hiku Ptah), the “Mansion of the soul, or ka, of Ptah”.[40]

It seems that a clue to the origin of miṣr comes from מצרים or miẓrāyim, the Hebrew name for Egypt. While discussing the word mdr, which means ‘enclosed’ or a ‘walled district’,[41] Spiegelberg pointed out that Egyptians built large fortifications to protect themselves from their enemies in the East attacking the fertile Nile Delta.[42] Wallis Budge noted that this word may have been the origin of Hebrew word מצרים for ‘Egypt’ in respect of its double wall.[43] Note that miẓrāyim comes with the dual suffix -āyim, perhaps referring to the ‘two Egypts’ – Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt or the double wall or both.

‘Egypt’ is referred to as miṣr in the Qur’an. This article dealt with the antiquity of the name miṣr for ‘Egypt’. It was noted that the diplomatic correspondence, written in cuneiform inscriptions, between ancient Egypt and neighbouring rulers indeed used the name miṣr for denoting Egypt. It was noted that ‘Egypt’ was called mi-iṣ-ri-i (with mi-iṣ-ṣa-ri as a variant) in the royal cuneiform inscriptions from ancient Egypt.

In our earlier study it was noted that unlike the Bible, the Qur’an mentions that there was only one Pharaoh during the time of Moses, i.e., the Pharaoh who was present during the time of Moses was the same one who died while pursuing the Children of Israel. Our analysis suggested that it was Pharaoh Ramesses II. As mentioned earlier, the cuneiform inscriptions from his time use mi-iṣ-ri-i to refer to ‘Egypt’. This usage goes back to the Old Babylonian Period (1950–1530 BCE) suggesting that it was also used during the time when Joseph was in Egypt presumably during the Hyksos rule (c. 1674-1553 BCE).

Acknowledgements

Images of cuneiform texts were obtained from the website of the British Museum, London.

References & Notes

[1] Muhammad Fuʾad ʿAbd al-Baqi, Al-Muʿahjam al-Mufahris li al-Fadh al-Qurʾan al-Karim, 1997, Dar al-Fikr, Beirut (Lebanon), p. 842.

[2] E. M. Badawi, M. Abdel Haleem, Arabic-English Dictionary Of Qur’anic Usage, 2008, Handbuch Der Orientalistik: Volume 85, Brill: Leiden & Boston, p. 886.

[3] Egyptians and Egypt were sharply distinguished from foreigners and foreign lands in speech and writing, and also in art, but here in more specific ways. The hostility expressed towards foreigners in Egyptian literature seems frequent, consistent and in modern sense downright disquieting. For details see D. O'Conner, "Egypt's Views Of ‘Others’", in J. Tait (Ed.), ‘Never Had The Like Occurred’: Egypt's View Of Its Past, 2003, UCL Press: London (UK), pp. 155-185.

[4] For a scholarly yet brief introduction of these letters, please see the following references: W. L. Moran, "Amarna Letters", in D. B. Redford, (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, 2001, Volume 1, Oxford University Press: New York (USA), pp. 65-66; M. Liverani, "Amarna Letters" in K. A. Bard (Ed.), Encyclopedia Of The Archaeology Of Ancient Egypt, 1999, Routledge: London and New York, pp. 150-153; "Amarna-Briefe" in W. Helck & E. Otto (Eds.), Lexikon Der Ägyptologie, 1975, Volume 1, Otto Harrassowitz: Wesbaden, col. 173-174; "Amarna Letters" in I. Shaw & P. Nicholson, The British Museum Dictionary Of Ancient Egypt, 2002, The American University in Cairo Press: Cairo (Egypt), p. 27; "Amarna Letters" in M. R. Bunson, Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, 2002, Revised Edition, Facts On File, Inc.: New York (USA), p. 24.

[5] The Amarna Letters are usually identified with a ‘EA’ prefix followed by a number. For details see W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore (USA) & London (UK).

[6] ibid., pp. xxxiv-xxxix, for the chronology of the Amarna archive.

[7] G. Beckman, Hittite Diplomatic Texts, 1996, Writings From The Ancient World - Volume 7, Scholars Press: Atlanta (GA), pp. 121-132; D. D. Luckenbill, "Hittite Treaties And Letters", American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, 1921, Volume 37, No. 3, pp. 190-197.

[8] T. Bryce, Letters Of The Great Kings Of The Ancient Near East - The Royal Correspondence Of The Late Bronze Age, 2003, Routledge: London, pp. 70-88 for the chapter "The Club Of Royal Brothers". Also see S. Jakob, "Pharaoh And His Brothers", British Museum Studies In Ancient Egypt and Sudan, 2006, Volume 6, pp. 12-30.

[9] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. xxxix.

[10] S. A. B. Mercer (Ed.), The Tell El-Amarna Tablets, 1939, Volume 1, The Macmillan Company of Canada Limited At St. Martin's House: Toronto (Canada), p. 2. Also see J. A. Knudtzon, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln Mit Einleitung Und Erläuterungen, 1915, Volume 1, J. C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, p. 60.

[11] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. 1.

[12] P. A. Clayton, Chronicle Of The Pharaohs: The Reign-By-Reign Record Of The Rulers And Dynasties Of Ancient Egypt, 1994, Thames and Hudson Ltd.: London (UK), p. 112.

[13] J. D. Hawkins, "The Arzawa Letters In Recent Perspective", British Museum Studies In Ancient Egypt and Sudan, 2009, Volume 14, p. 74.

[14] S. A. B. Mercer (Ed.), The Tell El-Amarna Tablets, 1939, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 182. Also see J. A. Knudtzon, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln Mit Einleitung Und Erläuterungen, 1915, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 270.

[15] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. 101. Also see J. D. Hawkins, "The Arzawa Letters In Recent Perspective", British Museum Studies In Ancient Egypt and Sudan, 2009, op. cit., p. 77.

[16] S. Langdon, A. H. Gardiner, "The Treaty Of Alliance Between Ḫattušili, King Of The Hittites, And The Pharaoh Ramesses II Of Egypt", Journal Of Egyptian Archaeology, 1920, Volume 6, No. 3, pp. 181-183 (transcription of the cuneiform inscription), pp. 186-192 (translation). The material above is taken from p. 181 and p. 187. Similar translations are also to be seen in D. D. Luckenbill, "Hittite Treaties And Letters", American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, 1921, Volume 37, No. 3, p. 190; J. B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts - Relating To The Old Testament, 1969, 3rd Edition With Supplement, Princeton University Press: Princeton (NJ), pp. 201-203.

[17] P. A. Clayton, Chronicle Of The Pharaohs: The Reign-By-Reign Record Of The Rulers And Dynasties Of Ancient Egypt, 1994, op. cit., p. 140.

[18] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. xxxix.

[19] P. A. Clayton, Chronicle Of The Pharaohs: The Reign-By-Reign Record Of The Rulers And Dynasties Of Ancient Egypt, 1994, op. cit., p. 120.

[20] S. A. B. Mercer (Ed.), The Tell El-Amarna Tablets, 1939, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 58. Also see J. A. Knudtzon, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln Mit Einleitung Und Erläuterungen, 1915, Volume 1, op. cit., pp. 126-127.

[21] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. 38.

[22] ibid., p. xxxix.

[23] S. A. B. Mercer (Ed.), The Tell El-Amarna Tablets, 1939, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 24. Also see J. A. Knudtzon, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln Mit Einleitung Und Erläuterungen, 1915, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 84.

[24] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. 16.

[25] T. Bryce, Letters Of The Great Kings Of The Ancient Near East - The Royal Correspondence Of The Late Bronze Age, 2003, op. cit., pp. 100-112 for the chapter "The Marriage Market".

[26] S. A. B. Mercer (Ed.), The Tell El-Amarna Tablets, 1939, Volume 1, op. cit., pp. 92, 94. Also see J. A. Knudtzon, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln Mit Einleitung Und Erläuterungen, 1915, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 178.

[27] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. 61.

[28] Y. Goren, S. Bunimovitz, I. Finkelstein, N. Na'aman, "The Location Of Alashiya: New Evidence From Petrographic Investigation Of Alashiyan Tablets From El-Amarna And Ugarit", American Journal Of Archaeology, 2003, Volume 107, pp. 233-255.

[29] G. G. Singer, "Some Economic Terms In The Amarna Letters", Cahiers Caribéens d'Egyptologie, 2005, Volume 7-8, pp. 197-205.

[30] S. A. B. Mercer (Ed.), The Tell El-Amarna Tablets, 1939, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 190. Also see J. A. Knudtzon, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln Mit Einleitung Und Erläuterungen, 1915, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 278.

[31] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. xxx.

[32] ibid., p. 100.

[33] S. A. B. Mercer (Ed.), The Tell El-Amarna Tablets, 1939, Volume 1, op. cit., p. 182. Also see J. A. Knudtzon, Die El-Amarna-Tafeln Mit Einleitung Und Erläuterungen, 1915, Volume 1, op. cit., pp. 268-269.

[34] W. L. Moran (Ed. and Trans.), The Amarna Letters, 1992, op. cit., p. 100.

[35] For a detailed lexical discussion on this issue see A. Erman & H. Grapow, Wörterbuch Der Aegyptischen Sprache, 1971, Volume 5, Akademie-Verlag: Berlin, pp. p. 122-130.

[36] A. Jeffery, The Foreign Vocabulary Of The Qur’ān, 1938, Gaekwad's Oriental Series - Volume LXXIX, Oriental Institute: Baroda, p. 266. Reprinted recently as A. Jeffery (For. G. Böwering & J. D. McAuliffe), The Foreign Vocabulary Of The Qur’ān, 2007, Texts And Studies On The Qur’ān - Volume 3, Leiden: Boston, p. 266.

[37] H. Zimmern, Akkadische Fremdwörter Als Beweis Für Babylonischen Kultureinfluss, 1917, J. C. Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung: Leipzig, p. 9. Also see J. Black, A. George, N. Postgate (Eds.), A Concise Dictionary Of Akkadian, 2000, 2nd (Corrected) Printing, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden, p. 220; M. Civil, I. J. Gelb, A. L. Oppenheim, E. Reiner (Eds.), The Assyrian Dictionary Of The Oriental Institute Of The University Of Chicago, 1977, Volume 10, Part 2, Oriental Institute: Chicago & J. J. Augustin Verlagsbuchhandlung: Glückstadt, p. 116.

[38] E. W. Lane, An Arabic-English Lexicon, 1968, Volume 7, Librairie Du Liban: Beirut (Lebanon), p. 2719.

[39] M. Civil, I. J. Gelb, A. L. Oppenheim, E. Reiner (Eds.), The Assyrian Dictionary Of The Oriental Institute Of The University Of Chicago, 1977, Volume 10, Part 2, op. cit., p. 113.

[40] "Egypt" in M. R. Bunson, Encyclopedia Of Ancient Egypt, 2002, Revised Edition, Facts On File, Inc.: New York (NY), p. 115.

[41] A. Erman & H. Grapow, Aegyptisches Handwörterbuch, 1921, Verlag Von Reuther & Reichard: Berlin, p. 75; A. Erman & H. Grapow, Wörterbuch Der Aegyptischen Sprache, 1971, Volume 2, Akademie-Verlag: Berlin, p. 189, 6; R. Hannig, Die Sprache Der Pharaonen - Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch - Deutsch (2800-950 v. Chr.), 2006 (Marburger Edition), Kulturgeschichte Der Antiken Welt - 64, Verlag Philipp Von Zabern: Mainz, p. 404.

[42] W. Spiegelberg, "Varia" in G. Maspero, Recueil De Travaux Relatifs A La Philologie Et A L'Archéologie Ègyptiennes Et Assyriennes, 1899, Fascicules I et II, Librairie Émile Bouillon, Éditeur: Paris (France), pp. 39-41, esp. 40.

[43] E. A. W. Budge, An Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary, 1920, Volume 1, John Murray: London, p. 338.